So you made an awesome track using a sample from another piece of music by another artist, and want to shop it to labels to release it for profit – what do you do next? Artists like Vanilla Ice, Two Live Crew, Bashmore, and Baauer have all faced allegations of unlawful sampling with some cases even going to the US Supreme Court. As a small time or professional producer how do you approach sampling and when do you decide that it is in your best interest to get sample clearance? Read on to find out from guest writer, lawyer, and producer Saleem Razvi.

“[In] truth, in literature, in science and in art, there are, and can be, few, if any, things, which in an abstract sense, are strictly new and original throughout. Every book in literature, science and art, borrows, and must necessarily borrow, and use much which was well known and used before.” – Emerson v. Davies, 8 F.Cas. 615, 619 (No. 4,436) (CCD Mass. 1845)

This article does not constitute legal advice + should serve as a guide for clearing a sample.

URBAN LEGENDS OF SAMPLING

Sampling and artist influences are always a part of the music-making process, consciously or subconciously. Before 1991, it was a sample-whatever-I-get-my-hands-on music world. Biz Markie and Warner Bros. were hit with a lawsuit and an injunction, which a pulled a track off Biz Markie’s third album. The presiding judge in this case even referred them for criminal prosecution, stating, “Thou shall not steal.” Shortly after, MC Hammer and Vanilla Ice found themselves in trouble with Rick James, Queen and David Bowie for unlawful sampling.

Everyone has heard the myths on sampling:

- I sampled only 4 bars, or 8 bars!

- I changed the sample by using FX so I am good to go!

Actually, if the sample is identifiable – no matter how short in length – you should get clearance. It could even be one note! Beastie Boys suffered a setback in the 90s for a six second, three note sample in Pass the Mic. The court ruled in favor of the Beastie Boys, since the sample was minimal and the listener would not recognize the original composition. Most producers don’t have the budget of MCA, Adrock, and Mike D -and their case shows how far a songwriter will go to protect their work.

If I don’t sell enough copies or make any money, the record company or publisher won’t come after me, right?

While this can be true, rights owners can still write to labels and websites and get your music taken down. This also affects your bargaining position if the track is successful. Just because something is on the internet doesn’t grant full permission for sampling. For example, using sample from an interview could allow the interviewee person to pursue legal action under state privacy laws for using their likeness.

Baauer is facing the prospect of a large settlement after Harlem Shake went viral and the original artists heard their voices sampled. Baauer could have paid a significantly lower amount to clear his vocal samples. So, what does it take to get a sample cleared and when should you do it?

WHAT’S COPYRIGHT ANYWAY?

Just a quick explanation here: copyright is not just a form you fill out, it exists prior to that. When a piece of art is put into a fixed form, (ex. download link, streaming sample) most copyright law protections kick in. When you fill out the official forms and register your art – that’s is when you get a presumption that you own the copyright to that work.

If you are dealing with a larger label they will ask you if you are using samples and if they are cleared. Even if they don’t ask, in the contract it will state that you, the artist, are responsible and present to them a clear and free work. If you are using a sample pack, check what the license says –especially if it involves vocals.

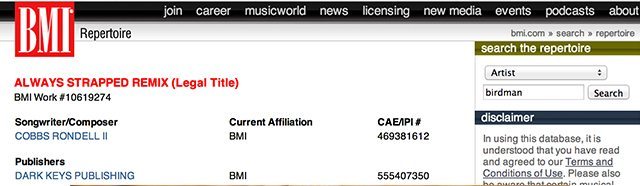

STEP 1: RESEARCH

Where do we start? There are two types of sample clearance:

- the master composition

- the sound recording

Start by researching the artist and track you plan to sample. Start with the major rights organizations like such as ASCAP, BMI, EMI or SESAC. Go to the repertoire and search the title or artist name, revealing the track title, performer, and the song writer(s), as well as the publisher names.

The listings give the publisher’s name and songwriter information, so next you need to search for the publisher on the net. Some of the larger publisher sites offer a mechanical licensing option (for cover songs) through the website. Record label information can be found just by pulling the song up on any music download site. Most old record labels have sold their rights to larger agencies.

NEXT STEP: CONTACTING THE PUBLISHER OR OWNER

The next step: find the licensing point of contact or a general information email to send your request. In your request you’ll want to include:

- all the information found on the ASCAP/BMI site

- what you sampled (how long the sampled portion is, time, seconds/bars)

- a private link to your track

- the length of the track

- what the tentative release date is.

If you cannot find the publisher’s information, do not get a response, or just have a phone number, don’t be afraid to call to get the correct contact information! Yes, these companies may not be worried about your downloads (since no one is getting rich from electronic music sales alone), but it doesn’t hurt to make and record the attempt.

Don’t worry that you won’t be able to pay an upfront fee, ask and negotiate if they will take a percentage of the royalties. As long as you show them that there is something in it for them and have done the groundwork, it will be easier to negotiate. Be up front. Some of them are not used to dealing with electronic music artists and think that the label you are working with has a budget for every release. Some companies may not want to deal with sample clearance and treat it just like a cover song or mechanical license.

These are controlled by statutory royalties and sometimes covered by the distribution site as well. Communicate with them and make sure they are the sole owners of the song. On one of my recent releases, the sample I used is actually 71% owned by one company and 29% by another. Sometimes a record label may also be involved if the ownership is separate – you’ll have to go through the same process with them.

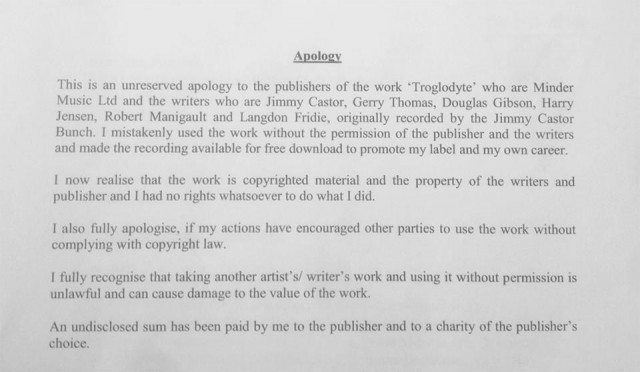

STUCK WITH NO RESPONSE

What if they don’t respond? Consider releasing the track as a bootleg or free download, not making a profit off the track but can get the exposure. This is how artists like Morgan Page got their start – but it could also end with a public apology for taking someone else’s work. Julio Bashmore found himself in this predicament and paid an undisclosed amount to the original songwriters (see his public apology below).

Finally, consider recreating the sample. Use different instruments or a similar sequence; try making it different. If you have access to live instrument players, then it can be treated just like a cover song. Once a song or track is out, it can be covered by anyone and performed as long as the statutory royalty rate is given to the original artists or copyright owner.

THE COPYRIGHT DILEMMA

Is it fair to use someone else’s hard work without paying them? Music is a creation that represents the artist and belongs to everyone’s ears, but when it comes to paying the bills, everyone is willing to go the extra mile to protect their work.

In my latest track (“Fire” produced with David Mel), I asked myself – can this be cleared, or can it be recognized? I started the conversation early on with the owners – so when a label came knocking (and later on Ministry of Sound!) we had the license paperwork ready to go. If you have a hit on your hands, why wait to clear the sample at a later point in time when it could cost a ton less to clear it early? If they can smell the money, sample owners are going to want a larger chunk.

Remember that every country has different laws, treaties, etc. that cover copyright law. As a disco house producer, samples are a part of the business. It’s not always worth it to obtain sample clearance, but if it is a well-known song, strongly consider it. Protect yourself by weighing the options in a world where technology like Shazaam can easily recognize bits and pieces of music and the copyright landscape is always evolving!

- Learn more about US copyright.

- Pay someone else to do it for you: sample clearing services like Music Clearance or DMG Clearances.

Saleem Razvi is a producer, DJ, and attorney – check out his production work here on Soundcloud.