The world of intellectual property law is quite relevant to musicians, especially DJs and producers that sample other people’s material in performance and composition. In this article, we provide some general tips for navigating this confusing, potentially treacherous landscape, so read on as we explain the basics behind laws that apply when remixing in your bedroom or playing a mashup routine live.

Please be aware that this article is written from the perspective of United States law. The spirit of most other national copyright laws is similar that of the U.S, but there are often important differences.

The Basics of Copyright

A copyright is an exclusive right, granted by the government, to the author of a particular work. This includes (among other things) the right to copy and distribute the work, the right to be credited for the work, and the right to determine who may publicly perform, adapt, or benefit financially from the work. For the purposes of this article, you can think of a “work” as a song. However, the copyright to a musical composition covers not just the final mix, but all of the original stems in a master recording as well!

There are two “sides” to music copyrights: a master side and a publishing side. I’ll go into greater detail later, but for now it’s enough to know that the master side covers the sound recording (and every stem used in the mix of that sound recording), while the publishing side covers the underlying composition (the music and lyrics upon which the sound recording is based).

“Infringement” is the legal term for violating someone else’s copyright.

This might take the form of (among other things)

- illegally copying or distributing a song

- failing to give proper credit to the owner of a song

- playing, remixing or financially exploiting a song without proper permission.

The implications of all of this may come as a surprise, but before you faint with concern that your next gig will be in the prison yard, take a deep breath. Unless you’re running PirateBay, MegaUpload, TorrentVortex or another nefariously-named haven of content theft, it’s unlikely that you’ll be making new friends behind bars (at least as a result of your musical endeavors). However, if you want to:

- avoid being sued for copyright infringement

- make as much money as possible from your own originals and remixes

Then continue reading for tips to help you navigate and take advantage of copyright law!

Production

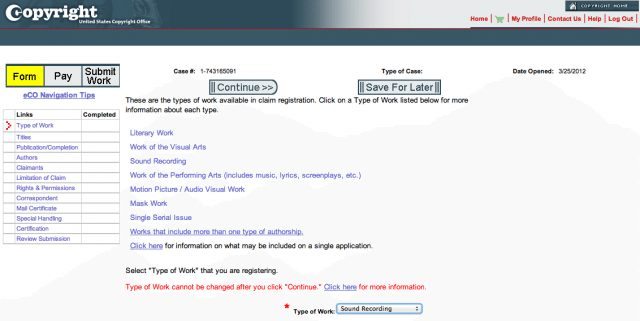

If you write and produce music, you probably already know that registering a copyright in the States is pretty easy. You fill out a form at copyright.gov, pay $40, and send two hard copies of your work to the U.S. Copyright Office.

In typical government fashion, it takes the bastards between four months and four years to make things official, but your copyright will run from the date they receive your application. I’d strongly recommend doing this for any original music you produce. Also, be aware that master and publishing copyrights are registered separately.

Official Remixes

Using and protecting music that you create from scratch is a bit of a no-brainer. Remixes are more complex. Legally speaking, a remix is a “derivative work”; that is a new work based upon an original work. According to the letter of the law, you need permission from the copyright holder of the original work in order to create a derivative work.

If an artist or label sends you a song to remix, that probably constitutes sufficient permission to create a derivative work (though it’s a good idea to at least have some written record of that permission – even it it’s just an e-mail). What an official remix opportunity like this doesn’t always do is determine who will own the resulting remix.

As mentioned, the master side of a copyright covers every stem in the mix, and the publishing side covers the lyrics and music. Since your resulting remix is likely to be comprised of stems, lyrics and music from the original combined with new stems and new music written by you (or a third party), the resulting ownership breakdown is by no means obvious.

Many artists/labels will address this complication by paying you a flat fee in exchange for your release of all rights to the remix. That saves a considerable accounting headache for the label and these days may be as much as you’re ever likely to see from royalties anyway.

Be aware that these sorts of issues are negotiable.

You can and should discuss copyright issues with the owner of the original song. By doing an official remix, you’ve written at least part of a new song, which means that you’re entitled to a proportional part of the publishing side of the new copyright. If you’re not being paid anything up front, that’s all the more reason to ask for this.

If you’ve produced original stems that went into the remix, you theoretically own part of the new master also. The problem here is, if an artist/label releases your remix as part of an album or EP, adding you to their accounting program and paying you a fractional royalty percentage will be very annoying (and it’s something many smaller labels are just not equipped to do). Paying percentages on the publishing side of a copyright is less of a headache for labels because performance-rights organizations like ASCAP, BMI and SESAC do most of the dirty work. Just make sure you register with them if and when you do receive a songwriting credit, otherwise they feed your royalty to Marc Anthony.

Copyright When Playing Out

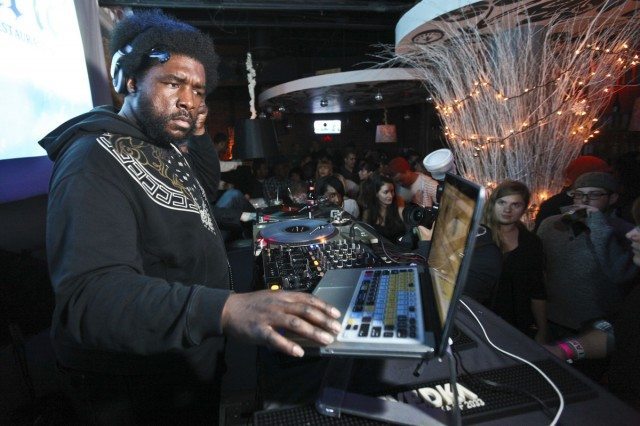

Live performance is a different story altogether. If the songs you play are your own, there’s likely nothing to worry about. With most DJs, unless you’re Daft Punk or Deadmau5, this is probably not the case. When you play other peoples’ music, there are copyright implications. In that situation, the artist whose music is being played is entitled to a public performance royalty (again, generally handled through ASCAP or BMI).

Fortunately for you, industry custom dictates that these royalties are the responsibility of the club, not the DJ. If you’re mixing songs and not just playing out full tracks, there are additional considerations to be aware of. Creating a live remix during one of your sets is not usually a problem, provided that you own the mp3s, CDs, or vinyl that you’re using and the venue at which you’re mixing pays the appropriate public performance royalties. Selling or distributing a live or unofficial remix, however, brings in a different set of rules.

Bootleg Remixes

The copyright significance of unofficial (bootleg) remixes is complex and ultimately depends to a large degree on what you’re trying to do with the remix in question. When you remix a song, you’ve created what copyright law calls a “derivative work”. Generally, one is supposed to have permission from the original copyright owner to create and/or distribute that derivative work. Without this permission, you’ve committed infringement.

There is, however, a doctrine of copyright law called Fair Use that creates a limited exception to this rule.

Fair Use is a defense to copyright infringement designed to encourage innovation, parody, and other beneficial results. The applicability of Fair Use to a given case is analyzed through four questions, which I’ve contextualized below. Here are the questions as they would relate to an unofficial remix:

- What was the purpose of the remix? If it can be viewed as a progression or commentary on the original, you’re better off than if it simply tries to “cash-in” on a tune that someone else wrote.

- What was the availability of the original song, and had it been released yet? It’s tougher to claim Fair Use if your remix is based on an advance or an unreleased track, because copyright law strives to protect the decision-making process of the original author as he decides whether or not to make his work public.

- How much of the original song did you use in your remix? Looping just two bars of bass from the original with a host of new stems is much more likely be viewed as Fair Use than playing a song start-to-finish and adding a few vocals.

- Has your remix diminished the value of the original song to the copyright holder? This isn’t confined to the idea that people might prefer the remix to the original when buying a record (since everyone’s doing so much of that lately); it’s relevant to licensing opportunities in film, television and commercials as well.

You get the idea- there’s no quick or easy way to determine if the Fair Use defense will work to protect you from copyright infringement. The answers to the above questions are balanced among each other, and no individual answer makes or breaks the case. Additionally, know that Fair Use is an affirmative defense, like claiming insanity at a criminal trial. It is you (the alleged copyright infringer) that must prove your remix fits within Fair Use; no one will assume it to be so.

Lessons From The Past

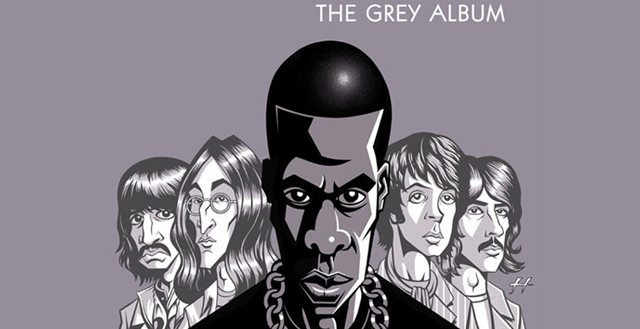

Many of you will remember Danger Mouse’s 2004 mash-up album of Jay-Z and The Beatles, The Grey Album. It was a massive internet sensation, critical success, and also was distributed for free.

Many of you will remember Danger Mouse’s 2004 mash-up album of Jay-Z and The Beatles, The Grey Album. It was a massive internet sensation, critical success, and also was distributed for free.

However, Danger Mouse didn’t clear the samples. While Jay-Z and Paul McCartney both made public statements in approval of the Grey Album, EMI (owners of the Beatle’s White Album masters) raised a legal hell-storm and put the fear of god into anyone and everyone who had a hand in distributing MP3s from the Grey Album.

EMI eventually backed off, and Danger Mouse got away unscathed. Some say this was because the Grey Album constituted Fair Use; others say it was due to the horrifically bad publicity EMI would have received if they’d proceeded; still others believe EMI eventually crumbled under pressure from their stable of artists (wishful thinking, if you ask me).

Two important takeaways from this tale: first, always remember that an artist’s permission to remix or distribute a song may very well be meaningless. Many artists (even big ones) don’t own their own masters – at least not outright. Second, in the world of copyright infringement, being an artistic revolutionary is much safer than being a profiteer.

We’re excited to have brought you this article based on your feedback – do you have a legal-related issue that you want an article written about here on DJTT? Hit up our User Voice page!

Want to read more about The Grey Album and download it if you were under a rock in 2004? Check out Illegal Art’s page devoted to exactly that.

Finally, if you’re interested in additional writings on where entertainment, life, and laws intersect, check out Noah’s blog, LawCue.