One of your main challenges as you learn how to DJ is figuring out how to take two totally different songs and make them sound as if they were designed to fit together. Maintaining the musical pace and feel in a mix is a very important facet of DJing that everyone, beginners to advanced, need to understand. As you learn how to DJ, you’ll discover all forms of music have an ingrained pattern of rhythm, tension and release that the dancers naturally follow and expect to hear. When those patterns are broken in a mix, it can seriously throw off the groove. Using those patterns to your advantage, however, will keep the dancefloor rocking early into the morning.

If you’re looking for more tips on how to DJ, I’d recommend checking out the following articles:

- How to Mix Pop Music

- Digital DJ Fundamentals – Sonic Mixing

- EQ Mixing: Critical Mixing Techniques and Theory

How to DJ: Understanding Phrases

8-16-32

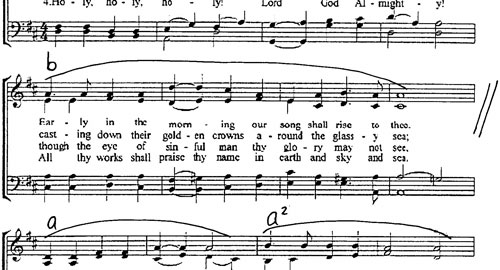

Most Western music is built using phrases of 8, 16 and 32 counts, which I am going to refer to as the “rhythmic structure.” The brain naturally expects these patterns, so as a rule you need to always keep each song’s rhythmic structures in sync with each other. The rule can be broken for creative effect, but it’s important to learn the rules of the road before you start breaking them. To match up rhythmic structure, you need to identify the individual characteristics of each song you are working with. That’s the easy part because every song contains audible clues that basically yell, “Hey, everyone, this is a new part!” These clues might include a new instrument that starts playing, a big crash, a drum fill or even just a significant change in the drum patterns. Electronic music loves to steadily add and subtract different parts every 32 counts, making it easy to recognize and work with those changes.

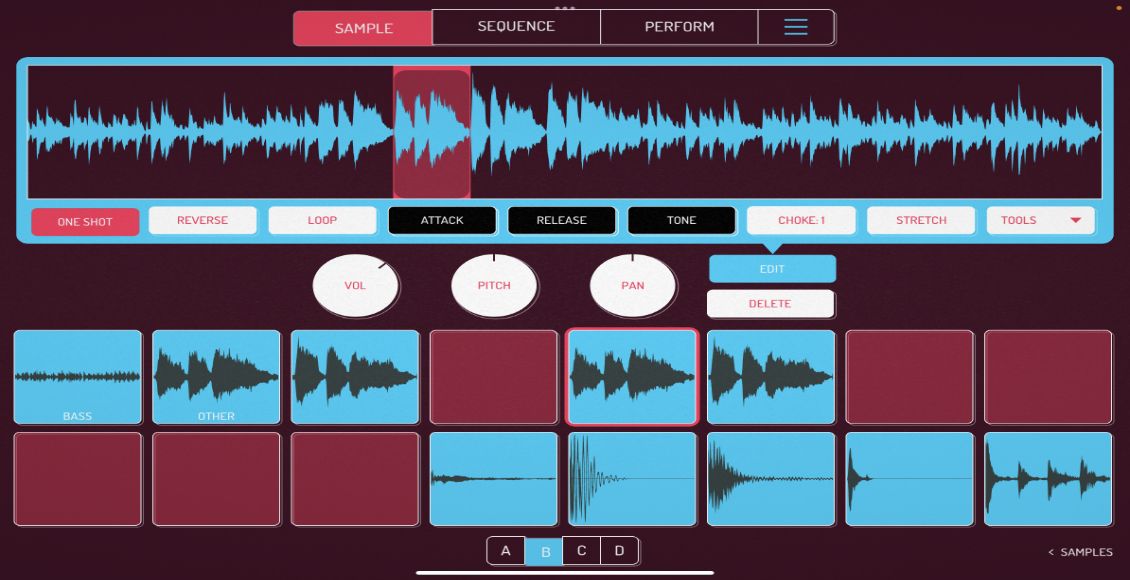

The general rule of thumb is to always start the new song at the beginning of a phrase in the outgoing track. Usually, that’s a fairly simple affair; it’s just a matter of training your ears to recognize the changes and patiently wait until the right time to start your mix. Most songs faithfully follow the 32-count rule, so as long as you get both songs’ 32-count rhythmic phrases in sync, then the tracks’ production takes over to help make the mix work for you. Occasionally, however, songs may make use of shorter phrasings, especially in hip-hop and pop songs, where an 8- or 16-count intro is more common. In those cases, you will need to time when you start the song so that the songs’ parts line up, or you can use loops to extend the intro and give you a longer mix. As an example, we’ll look at a typical hip-hop/pop scenario.

THE POP PHENOMENA

Almost every pop song has a short nonlyrical intro, a verse and then a chorus. Generally speaking, you always want to mix “out of the chorus” so that the audience gets the big musical payoff and then you are into a new song afterward. Because the intro is usually the only part of the songs without lyrics, you are basically stuck mixing intros over the chorus all night.

Most intros are 16 counts long, while the typical chorus will last for 32 or 64 counts, so you can’t start an intro right at the beginning of the chorus. If you did that, your verses and chorus will start slashing with multiple people singing and/or rapping at the same time. It’s essential to time it so that the first verse of your new song starts right as the old chorus ends. Timing it that way will make such a “quick mix” feel completely natural and will seamlessly blend together the musical structures of each song. Your alternative is to use cue points and loops to extend an intro over the top of a chorus and then effortlessly drop into the new song at the right time.

I am going to call that rule “respect the chorus” so it reminds you to always pay attention to how you’re mixing in relation to the chorus of a song. This rule applies just as much to electronic music as it does to pop songs. Most good underground tracks give you a sense of having a chorus or a peak moment of a track; that’s what makes them good “songs” and not just random collections of notes and beats. It goes without saying that you would not want to cut off any tune before that big payoff, so even in the most minimal of tracks always respect the chorus. That does not mean to mix only during the intros or outros of a track either because that leads to a dip in the energy and a really boring mix.

When mixing vocal music in the way I’ve discussed, the new track’s verse takes over for the old track’s chorus and carries the listener into the new song seamlessly. In the same way, you can use the musical parts in instrumentals by timing the start of a big part of your new song with the end of the peak moment in an outgoing track. Do all that while also bumping up into the next musical key to give the transition an extra lift, and you will be considered an official DJ maestro.