The moral acceptability of trainspotting (figuring out what a DJ is playing) is a longstanding debate in the DJ community. But in recent years, new tools and communities have changed how the process works – and one DJ, Jackmaster, took issue with it last week in a heartfelt opinion. Read on for a breakdown of what both sides of the issue think and to share your own opinions on the concept.

Trainspotting: The Bane of Professional DJs?

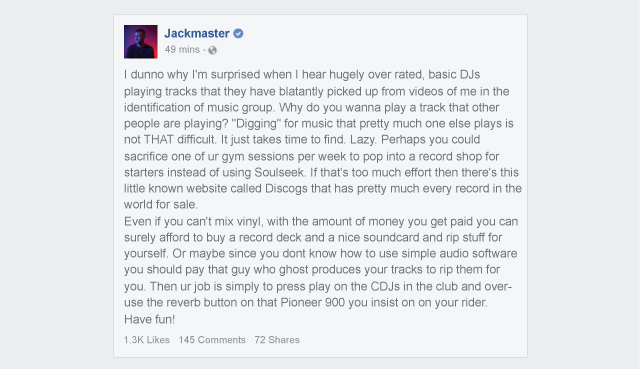

Last week, DJ Jackmaster went to Facebook to take to task DJs who have trainspotted his tracks and then played them out. These DJs allegedly used Facebook Groups dedicated to identifying tracks and posted videos of Jackmaster’s sets. The communities (thousands of music lovers) then all collaborate to find the names of the tracks that were played.

This is part of an ongoing and evolving debate on trainspotting. The music market is more saturated than ever, and the way we consume music is changing. Should trainspotting become less taboo? This article aims to take an objective look at Jackmaster’s post, while also diving into the debate to see what both sides have to say.

Trainspotting + Why DJs May Think It’s Rude

Back in 2015, DJTT editor Dan wrote an informative article on the topic of trainspotting – which included this description of trainspotting (in DJing) as defined by the great Urban Dictionary:

v: The act of staring over a DJ’s shoulder to see what records he’s spinning.

Originated from the British phenomenon of train geeks waiting on train platforms, notebooks in hand, recording the types and numbers of trains coming into the station.

Let’s break down why Jackmaster is peeved about DJs playing tracks from his sets. First of all, he states that “overrated, basic DJs” are playing tracks that (allegedly) “they have blatantly picked up from videos” of Jackmaster in The Identification of Music Group on Facebook.

Let’s assume that he’s a member of the group and saw videos of his sets being posted where people asked what tracks are being played at certain times. We can’t say for sure that these people asking or the are DJs lurking for new tracks to play, but it’s not an invalid concern. After all, if Jackmaster is a member of the group, who knows what other famous DJs might be on there trying to cop new tunes?

Who’s Doing The Track IDing?

The second point of contention is that the DJs have other people identify the song, versus the “traditional way” DJs find records to play – crate-digging. In the past, crate-digging literally meant digging through crates of records to find music, people now use online tools to find tracks.

Finding tracks can be a time-intensive process. As a DJ who plays a weekly radio show, I know the feeling of spending a few hours trying to find new music to play.

[clickToTweet tweet=”It can be infuriating to spend hours finding a rare track only to hear other DJs play it out later. ” quote=”It can be infuriating to spend hours finding a rare track only to hear other DJs play it out later after trainspotting your set. “]So if DJ A spends hours finding a specific track and other DJs start playing that same track after hearing DJ A‘s set, we can see how DJ A could be pissed off about DJs piggybacking of his track selection work.

Ripping Off The Work Of Ripping Records

The final issue brought up is specific to finding actual vinyl records and playing those out. It feels a bit overstated to stereotype trainspotting DJs as overpaid superstars, so for the purpose of this article, let’s ignore that and focus on the production work that goes into making recordings of rare vinyl records.

If you’re playing older tracks, you might find yourself in this position to want to get your vinyl collection into Traktor, Serato, or Rekordbox. Assuming the track is not available to download online, you have to buy the record, get a soundcard, and rip the song into a DAW to export the track as a WAV or MP3. Or, alternatively, the DJ could spin the record if there’s a record player in the booth and they know how to mix vinyl. The argument here is that DJs who opt to rip tracks from recorded DJ sets or download rare vinyl tracks from other sources are cutting corners and don’t respect the art of digging for tracks.

A few other reasons why some DJs believe this isn’t a cool practice:

- The act of trainspotting is like stealing material from another DJ (basically acting like the Amy Schumer of DJs)

- Discredits the amount of work other DJs put into finding tracks (check out our article on finding new tracks for an event).

- DJs may be playing tracks that aren’t released to the public or haven’t been announced by the label/artist.

- The track may have been gifted to the DJ as an exclusive remix/edit/mix from a producer.

- Piggybacks of the successful track selection of a DJ.

- A DJ is not obligated to share the names of the tracks being played. If they don’t want to share or publish a tracklist, they shouldn’t be criticized for not doing so.

Author’s Note: By listing the above, I’m not claiming to agree with them. The purpose is to show where other DJs may be coming from on the issue 🙂

Sharing is Caring: In Defense of Trainspotting

DJs are often some of the most enthusiastic and excited audience members when it comes to watching another DJ play. I like to carefully watch a DJ perform to learn from them and experience how another DJ throws down a set. One part of that experience is dissecting the track list.

As an audience member, a person who falls in love with a track that they never heard before will most likely want to know the name of the song. This audience member might not even be a DJ – but still want to listen to it at home.

[clickToTweet tweet=”DJs are displaying tracks like an art collector displays their painting collection.” quote=”DJs are displaying tracks like an art collector displays their painting collection.”]What is wrong with letting others know what tracks you played? Aren’t DJs meant to be the ones who open minds up to new music?

Now, DJs may want to know the name of the track so that they can play the song in their sets as well. DJ A hears DJ B play a track and thinks, “This house track is nuts! I want it for the club night I am playing at next weekend.” DJ A just experienced a moment of musical discovery just as DJ B did when she found the track on Soundcloud or Beatport. Sure, DJ B may have spent hours looking for tracks before coming across this awesome house track, however, DJ A didn’t come through DJ B’s set just to steal her tracklist to play at his event. He came for the music and left discovering something for himself. DJ B should be happy to expand DJ A’s mind to new music and the fact DJ A wants to the name of the track is almost flattering.

White Labels

Before the DJing scene exploded after the turn of the century, there was a lot of competition between DJs. One form of competition was the art of track selection. It wasn’t uncommon to hide or mislabel names of records to make sure that other DJs wouldn’t be able to “steal” the names of hard-hitting tracks. There was some validity to this practice – some songs and edits were only released in limited quantities. A DJ’s competitive advantage when it came to music was huge, especially when securing gigs and creating a career:

“Today’s notion of rarity is less about old gems and more about anoraked techno nerds championing unheard-of test-pressings by twelve-year-old geniuses on tiny labels based in garages in Canada, but the prestige of rarity introduced by northern soul has never left dance music.

Clubbers would journey hundreds of miles at the thought of hearing that one elusive disc. Posters included lists of the rare records you would hear at a particular event, and a DJ’s standing on the circuit could rocket overnight by the simple expedient of acquiring one desirable 45.” – From Frank Brougbton + Bill Brewster’s “Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc Jockey”

Fast forward to 2017 and DJ culture has changed drastically. The barrier to entry substantially lower and the market seems over-saturated with DJs who have the equipment to play a gig.

DJs are also downloading tracks versus going to the record stores to find new tracks to play. That time is now spent scrolling through Soundcloud streams and online music stores where anyone can download the tracks. There aren’t limited quantities of songs either. A DJ can’t justify having exclusive rights to playing a certain track when that track has thousands of plays on Soundcloud.

Two DJs who both play the same track aren’t (necessarily) playing the track in the same context. They will have different tracklists, and mix those tracks in a different style. With the exception of a DJ’s own remixes or edits that are made specifically for their set, tracks being played by a DJ are fair game for other DJs to play. A DJ uses a collection of other people’s work to build a new piece of art. Pieces of work in that collection are available to other DJs as well.

Here are a few arguments DJs defending trainspotting:

- DJs share music with an audience. DJs shouldn’t scold the audience (DJs or not) that wants to go out and buy the song they heard.

- DJs who play other people’s musical work (and who don’t own copyrights, etc.) don’t own the right to play it out. Therefore, they shouldn’t be upset when other DJs play the same songs.

- DJing is about sharing music with the world, not hoarding tracks so that people can only hear them through one DJ. (check out our new DJ Track Trade series.)

- In the digital age, songs aren’t rare commodities and can’t be contained to one or two DJs.

- A DJ discovering a track at a club isn’t very different from a DJ discovering a track on Soundcloud. It is just discovery through different mediums.

- Groups like The Identification of Music Group and apps like Kado are great tools for finding the names of new tracks; they aren’t malicious tools used to steal a DJ’s set.

- Producers appreciate their music being shared with the audience versus being hidden by the DJ. (Who is probably playing their music without permission.)

Author’s Note: Again, I’m not personally agreeing or disagreeing with the above – just listing out more opinions!

Everyone Prepares For Gigs Differently

Trainspotting continues to be an act that is seen differently in the eyes of many DJs. Beautiful music sharing to some and blatant laziness to others. While DJs will disagree about the ethics of trainspotting, no one can disagree that preparing for a gig is a lot of work.

Some DJs prepare by digging through dusty records in a vintage record store while others scroll endlessly on Soundcloud. No matter how one finds records to play, the art of creating a playlist for a gig is special for many DJs. We all do it in different ways – but no one should be shamed for wanting to play great tracks to a crowd.

Is trainspotting something that DJs shouldn’t worry about? Are DJs obligated to share their tracks with the audience? Share your thoughts in the comments.