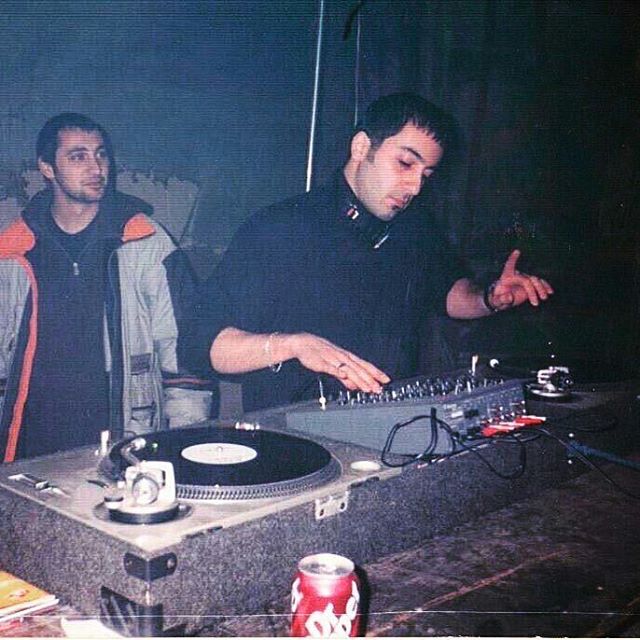

Growing up in Washington D.C. underground dance scene, Sharam Tayebi, has been an instrumental figure in house and techno music as a DJ, producer and one-half of the duo, Deep Dish. Akhil Kalepu sat down with Sharam at ADE 2017 to discuss his musical roots in Iran and how his DJ and production rig has changed over the years.

Who Is Sharam?

For readers who aren’t familiar with Sharam, here’s a quick background – via Wikipedia:

Sharam Tayebi, better known as Sharam, is an Iranian-born American techno and house DJ and producer. Born in Tehran, Iran, he emigrated to Washington D.C. as a child. A mainstay of the Washington underground dance music scene, he is a techno and house DJ and producer, both as one-half of the duo, Deep Dish and solo artist, producer and mixer.

As part of Deep Dish with Ali “Dubfire” Shirazinia, Sharam released two albums, and produced or remixed a library of other releases including those from Janet Jackson, Stevie Nicks, Rolling Stones as well as others. The duo received a Grammy nomination for their remix of Madonna’s “Music”, and won the “Best Remixed Recording” Grammy for their remix of Dido’s “Thank You.”

As a solo artist, Sharam released two of his own albums, six mix compilations, and produced or mixed fourteen other artists such as Bruno Mars, Coldplay, Steve Aoki, Shakira and more.

For this style of interview, we love to add a taste of the DJ’s mixing into the article. Embedded below is a recent mix of Sharam’s, recorded at Mixmag’s In The Lab LA series – tap play and then read the interview below:

How did you first get interested in electronic music?

Initially, as a kid growing up in Iran, my sister and her husband got this Betamax VCR, which at the time was revolutionary. Nobody had a VCR, but they had it and my brothers and sisters had music on cassette tapes. Post-revolution you couldn’t get music in Iran. Whoever had them, had them, if you didn’t you had to get a professional studio to copy a cassette. There were these double-cassette decks, but the price of getting them was like getting a car, so I was trying to figure out, how do I copy this stuff? How do I take some songs that I like and put them into another tape? I ended up using the VCR as a recording tool.

There were some underground video shops, like truly underground shops that were smuggling this stuff in. I would rent videos like “Top 20 Video Countdown” from MTV. I would take the sound and connect it to a cassette tape and record it. Now it sounds like, “big deal!”, but back then, in Iran there was nothing like that. I figured out how to do that and that’s how I sort of got involved with music. I would do underground parties where I would be the only guy that had this music, and I really loved the attention I was getting because of it! I got fascinated with that stuff, and when I came to America, it was like a sea of music.

I would spend half of every day in record stores. Then I discovered a dance record store and I was like: “Oh my god, this is it. This is a whole different game.” I was really fascinated with all this stuff, that’s why I got into DJing and turntables and mixers.

When did you first start mixing?

I would throw school parties just so I could DJ.

I was mixing in Iran, except they were not really mixes, they were “chops”. When I came to the U.S. I started making these tapes but they were mostly pop before I discovered dance music. Then I discovered this thing called a turntable and a mixer, where you could mix this stuff together.

I would make mixtapes, and I wanted to be a DJ. I would throw school parties just so I could DJ. I got a bit into promoting in D.C. at George Mason University. Throw parties, make a hundred bucks, spend a hundred bucks on records so that the next party you could play ten new records. Import records were like 10 bucks, which was a lot at the time, while domestic records were four bucks. So you would wait for some of the records you really wanted, the import ones to become domestic for a fraction of the price.

I would make these tapes and handed them to some clubs. They would ask me to come and audition and I ended up getting jobs and different places, that’s how I ended up in the DJing thing.

Do you remember the brand of the mixer and turntables?

Yeah, Realistic. Radioshack Realistic. The non-pitch control turntable was a Pioneer, it was part of one of those box sets with an amplifier, casette and a turntable on top. So my brother had bought me that, I said, “Okay, this is fantastic but I need one that has a pitch control!” They were like, “What are you talking about?” My friends chipped in and got the Technic SL-1200.

I only had the other turntable, so I learned how to mix with only one pitch control and I perfected my skills using that system. A lot of DJs use both turntables to change the speed, I always do it on one because that’s how I learned.

The Realistic mixer, which was only $80, but it turned out to be one of the best sounding mixers. We made the first Deep Dish album, Penetrate Deeper completely mixed on that.

How did you get into making your own records and remixes?

I met Ali through a mutual friend. I was throwing these parties and asked him to come DJ at my party. We had a lot of similar records that people were into like New York house, Detroit techno. I was more into the high energy stuff, he was more into trip-hop, acid jazz, rare groove, stuff like that. We had a lot of commonality but also a lot of differences in terms of what we were into at the time. He was into industrial music, which I [discovered] through him. He opened my eyes to a lot of stuff, I opened his eyes to a lot of stuff I was into.

We would listen to a lot of records and I was like, “We should try and make records!” He had some friends that had a studio. We went to the studio over the course of a week or two and knocked out four tracks. They helped us since we didn’t know our way around anything, but we knew what we wanted. We knew what needed to be done to these records, so we made them based on our influences. The first one ended up making a lot of noise, so we made another one, and another one and that’s how the whole thing started.

What were you using in the studio?

We were using our friend’s equipment. John Selway, who was a very proficient producer, and part of the Smith & Selway moniker, he and also BT were really the studio geeks at the time. So we used their studios and learned a lot of stuff from them. With BT we were using an MPC3000, and then we ended up buying one to use ourselves. Early on it was a 909, these IBM sequencers, very primitive. At the time, I didn’t understand any of that stuff. I just knew what was in my head.

I didn’t know any music theory. In fact, that was always one of the techniques that we had. Because I didn’t know any music theory, I would always have these crazy ideas, and everyone would be like “What are you doing? That doesn’t make any sense.” Ali had to be the in-between person saying, “Guys, just trust him”, and they would do it and it would turn out into something we never would have thought of. The unconventional way I was looking at it helped forge a sound that we weren’t even aware of making.

Later on we slowly got our own setup. Our first sequencer was Cubase. I remember the first equipment I bought was a Juno 106. I got it off one of those Want ads for four hundred bucks, the best thing ever. I was like, “Wow, I have a Juno!”

Do you still use your Juno?

Yeah! Still in my studio. I don’t use it as often because I’ve become very in-the-box. For me it’s all about time. Right now I love the way I can just basically make a track on my laptop, get on a flight, open it up, continue, get in a hotel, continue, bounce it, test it out that night. Next day, make changes, now in a weekend tour I can have a track finished without having to be in a studio.

I do my best work on shit flights.

I’m in the studio a lot, but more of my ideas are started on the road. Especially on shit flights. I do my best work on shit flights. There’s nothing more fun than starting a track from scratch on a flight, next thing you know three hours have passed and you have a complete, finished track.

What setup are you producing with on your computer?

I’m using Ableton. I used to use Logic a lot, but Ableton gives you the freedom to start projects fast. It gets what’s in your head down a lot easier, a lot more efficiently than Logic. I prefer Logic for arrangement, but there was a period where I was migrating projects from Live now and again. It’s all a matter of time and efficiency. I find if you really know what you’re doing, you can make a record sound just as good in Live as in Logic.

Any plugins you find yourself going back to?

I use a lot of Fab Filter. I use a lot of UAD. With UAD you must have the box with you, so usually I use the UAD stuff towards the end of the project. I use some Softube, Waves, SoundTools and also a lot of in-the-box stuff from Live and Logic. These are my go-to plugins. I’m not too much of a “gear-whore” if you will.

Once you’ve learned to use a compressor, they all pretty much do the same thing. It’s just a matter of how you use it, especially in the creative process. It doesn’t matter if you use a UAD or a regular compressor from Live. It really doesn’t matter. Maybe you’ll get it a little fatter, but it doesn’t matter unless you’re towards the end when you want to mix it. Now, I mix as I go along, but when you want to master it. I like to master so I can play it out. When the track is ready, I’ll send it to some professional person to master, but I’ve had my masters sometimes sound better than the professionals, and I’m like “Fuck, what do I tell this guy now?”

You produce your records with a mastering chain attached?

Yeah, I try to do that and mix as I go. Once I have half the project ready, I immediately go to arrange right away. That way the track will tell you where you need to put your focus on, and usually I like to play it out just to see how it sounds.

So yeah, I put a mastering chain. I have one I created and just dump it in, but it doesn’t work for everything. I like to just go through the process, put a limiter, an EQ, a little compression. I like to do that as I go along. One of the things I changed was that I used to start at 0 db for a track and redline like crazy. I’ve learned to start low, just from using other engineers, seeing what they do. As a DJ you always want volume, so when you’re making them you want them to sound loud too. Next thing you know there’s redline all over the place.

Over the years, has your live setup changed at all?

I used to play vinyl, then I went to burning CDs, then Traktor came along, which for me was revolutionary. Taking music, burning it onto CDs, writing what it was, that was a whole process. Traktor eliminated that, you could take a lot more music with you. By the same token, the more choices you have, the more confusing things can get. I love the idea of vinyl because you can only put 50 records in your box. Back in the day we used to travel with two of them. The idea was that to add five new records, you had to take five out. You were always optimized, the best records were always in your box. With Traktor there’s so much shit that you put in there. If you’re not disciplined about it, which 99 percent of DJs aren’t, including myself, next thing you know, you have so many records and then, “Oh shit, what am I going to play?”

How do organize your records and plan for sets?

I create playlists, but what I like as a DJ is the unpredictability. If I don’t buy new records, if I don’t get new promos, I feel like I suck as a DJ. The fact that there’s five or ten new records in my box rejuvenates my creativity and I program the night a lot better.

Create these playlists where it’s no more than 50 records

I’ve given this advice to people a lot. Create these playlists where it’s no more than 50 records. If you’re going to add some records in, then take some records out. I’m trying to discipline myself to stick to that philosophy. I [also] tag my records in a certain way. If I want to play a driving techno record with some melody in it, I type “driving, techno, melodic” and 50 records show up. It’s hard to remember names these days, unless it’s a specific producer that you like. Back in the day it was vinyl, so visually I would know the records. Now that doesn’t exist.

Do you mess with Stems or Remix Decks at all?

I did for a bit, but I found it to be distracting. It’s really cool to have a bunch of loops to play on top of each other. Sometimes technology companies consult with me, and [I tell them] “You cannot lose sight of what a DJ’s job is.” It’s to connect with the crowd and entertain and educate. When your head is in this box the whole time, there’s no room for connection. It’s like a robot playing.

Whatever technology comes my way, I try to keep my stuff as simple as possible. I’m not going to be a DJ who has too many things there. I see DJs using it but they’re not really using it, it’s just there for show. Maybe for a crash or snare or maybe create a loop. Theoretically it’s fantastic. I see some people creating a loop that gives it more energy – but you could easily record that [as a new track and play it] in Traktor.

What’s easier to do? What’s easier to travel with? The whole Stems thing was really a fantastic idea to break a track down into these components and play them individually, especially acapellas, a hook that’s fully recognizable. But 99% of the records out there, they all sound the same. What are you really taking out? It’s more like a novelty rather than a practical tool. I mean we supported it, we did it and I ended up not using it as much.

Any last tips or advice?

Don’t lose sight of what’s important. Making a record or playing for people, it’s entertainment. I always put as much value in the entertainment part of it as I do in the education part of it. I think a DJ’s responsibility is to not only entertain people but also educate them on new music. When people come to hear your music, but also come to be enlightened.

It’s important to do that and not just play your ten best hit records or the top ten Beatport or whatever. A lot of people do that because they want to enter with a bang and leave with a bang, but since everyone’s now doing that, people have caught on. So that’s the thing. Be true to yourself. Use technology as an enabler.

This interview was edited for clarity and length, special thanks to Sharam for sitting down with us at ADE!