Designing technology for performance and music making with is an art form. But until now, no one took on the challenge of chronicling the evolution of this design process. A new book, Push Turn Move, has just dropped – and it might be the most invigorating analysis of DJ and production gear design we’ve ever seen. Keep reading for a full review and insights from DJTT’s Markkus Rovito.

Push Turn Move: Interface Design in Electronic Music

Ever wondered how your favorite music hardware and software comes into being? Push Turn Move guides you into the design processes of some of the most iconic gear developers of all time, including Roland, Native Instruments, Ableton, Roger Linn, Elektron, Korg, Dave Smith, and many others. Yes, DJ TechTools made the cut as well. Through gorgeous photo spreads, exclusive interviews, and breakdowns of core design principles, Push Turn Move tells the story behind electronic music technology and how in the end, it is all done for you.

- Reviewed: Push Turn Move – Interface Design in Electronic Music

- Author: Kim Bjørn

- Price: $83 in the DJTT Store

When they hang out, designers really like to geek out with each other about design. That’s not the only thing they have in common with those of us who almost reflexively geek out about music gear if we’re around anyone of like mind.

In Kim Bjørn’s painstakingly crafted new book, Push Turn Move, we hear from several successful electronic musical instrument designers about the difficulty of knowing when to stop adding to or tweaking their designs. They also talk about the necessity of limitations and constraints when designing a musical interface to avoid the paralysis of endless possibilities.

In Kim Bjørn’s painstakingly crafted new book, Push Turn Move, we hear from several successful electronic musical instrument designers about the difficulty of knowing when to stop adding to or tweaking their designs. They also talk about the necessity of limitations and constraints when designing a musical interface to avoid the paralysis of endless possibilities.

Those exact sentiments echo loudly among electronic music producers, who often get bogged down in their endless possibilities. It can be hard to know when to let go of a piece of music and call it finished.

“To be creative, you often need many limitations. Suppose you have an endless canvas to work on – the result is you can’t even start. If your choices include everything, you’re not hungry anymore; you lose your appetite. Limitation is everything.” – Jesper Kouthoofd, CEO of Teenage Engineering

“In a lot of products, they just try to too put too many things in there… It’s a real problem with synthesizers, because they can do anything, and the hardest part of the design is knowing when to stop.” – Dave Smith, founder of Dave Smith Instruments and Sequential Circuits, key contributor to the MIDI spec

Such creative similarities help make a book like this—probably the only book specifically examining the principles, philosophies, and practical considerations of designing electronic music interfaces on this scale—so fascinating.

The author Bjørn is both an electronic musician and a designer, as are many of the creators profiled in Push Turn Move. And unlike genres that rely on basically stagnant instrument concepts like drums and guitars, electronic music as we know it today would not exist without the relationship between the ever-growing capabilities of music technology and the artists who inevitably find ways to use that technology that the creators never imagined.

Designers have plenty of thick, weighty, richly illustrated books like this one to refer to about architecture, home furnishings, and… fonts. Never get a designer started on fonts unless you have the next 25 minutes to spare.

But there’s no other book like Push Turn Move, which approaches musical interface design from academic, philosophic, practical, scientific, emotional, and even psychological points of view. It’s like the ultimate tome for true gear geeks, who always have some level of curiosity about how their tools are made. It should be required reading for anyone thinking of creating electronic music gear, whether that’s someone who’s immersed in the culture already or the percentage of people who work in the industry but are not musicians.

This book pulls the veil back on some of the product design and development processes at highly esteemed companies like Moog Music, Arturia, Korg, Novation, Elektron, Roland, Propellerhead, Native Instruments, and many others through more than 40 interviews with product creators, as well as some musical artists who have a deep affinity for and expertise with certain music technologies.

A framework of chapters surrounds those interviews and breaks down electronic instrument designs to their fundamental elements, in order to compare how different product examples handle those elements. Beginning with how instruments visualize the building blocks of sound—frequency, amplitude, notes, and duration—the book moves through the strategies for controlling sound: knobs, faders, buttons, pads, keys, wheels, joysticks, touch strips, capacitive controls, x/y pads, sensors, displays and menus.

Nearly every page spread in Push Turn Move gives you a visual feast of every type of electronic gear and software of the last 50 years, from modular synthesizers to iPhone DJ apps, including timely new releases from as late as mid-2017. Leafing through the pages feels like a tour through a museum installation; so many thoughtful designs alongside each other renews your appreciation for just how beautiful these machines and software programs can be. You’ll be reminded of lost classics, as well as modern marvels that have not yet received their due.

However, Bjørn never tries to present a complete list of music gear. Rather, he chooses examples to illustrate the design principles in question, regardless of whether that product was a success sonically or commercially. After all, design and product development conventions are just guidelines. Following them never guarantees commercial or critical success, nor does ignoring them always seal your doom. Stories from the book show how companies like Ableton and Teenage Engineering did things their own way and came out as industry darlings.

“[Ableton Live was] an almost literal translation of our personal music creation process… There was no consideration for how other users would perceive or understand any of this. There was no user research or usability testing. Of all the things that people now learn in school about UX design, we did nothing. We were lucky that our way of making music resonated with some other people.” – Gerhard Behles, co-founder and CEO of Ableton; former member of Monolake.

Music technology has the power to change music itself, whether things go well, as in the case of the MIDI standard, or occasionally when a product flops. Perhaps the most famous case of a spectacular failure goes to the Roland TB-303. It was made to be a bassline accompaniment for guitarists, who basically hated it. When it started showing up in the second-hand market, it helped the progenitors of acid house and techno shape those entire genres.

As Push Turn Move goes through the principles of effective instrument layout—contrast, grouping, alignment, size, placement, signal flow, simplicity, consistency, ergonomics, color, text, graphics, style, and historical identity—the sheer number of factors going into product design almost become dizzying.

“There are many examples of utterly failed interfaces, and electronic musical instruments in general seem prone to these two worlds of creativity and functionality colliding… simply because the musician isn’t always a technician, and vice versa.” – Daniel Troberg, CEO of Elektron, US division.

We all can think of some examples of poorly designed music gear, but while a truly boneheaded design probably does make it to market from time to time, products that miss the mark are likely more often the result of miscalculating a delicate equation with many data points going into it.

One of my favorite sections of the book comes at the beginning, where designers have to consider a litany of human limitations and preferences that will determine whether a product is something they want to use. A designer has to consider the context in which the instrument will be used, and how an individual user’s experience and skill level will affect their visual, cognitive, and physical capacities. An instrument should challenge those capacities without being too difficult. The right balance with the right workflow will help the user reach a creative state of flow, and when that happens consistently, the user develops a personal connection to the product.

To do that, a musical interface needs to be functional, reliable, and user-friendly first to move on to the higher goals of being enjoyable, creatively meaningful, and trustworthy to the point that the user anthropomorphizes the equipment as a friend, band member, etc.

This section reads like both an emotional love letter to music technology and a hyper informed practical examination of the human conditions that contribute to the acceptance of a piece of music technology. In the end, the users want what they want, and they are always correct in those desires. However, the endless variations of individual users’ knowledge and skill levels mean that endless variations in musical gear can both succeed or fail if they don’t pinpoint the balance properly.

Finally, a coffee-table book for music gearheads that you’d do well to actually read.

Interface Concepts

Nearly half the book examines different interface types that electronic music technology can embody. These include DAWs, step sequencing, grids, matrices, mixers, DJ systems, generic MIDI controllers, hybrid hardware/software gear, multitouch surfaces, user-configurable interfaces (like TouchOSC on iPad and the ROLI Lightpad Block), semi-modular, modular, DIY, and even coding languages.

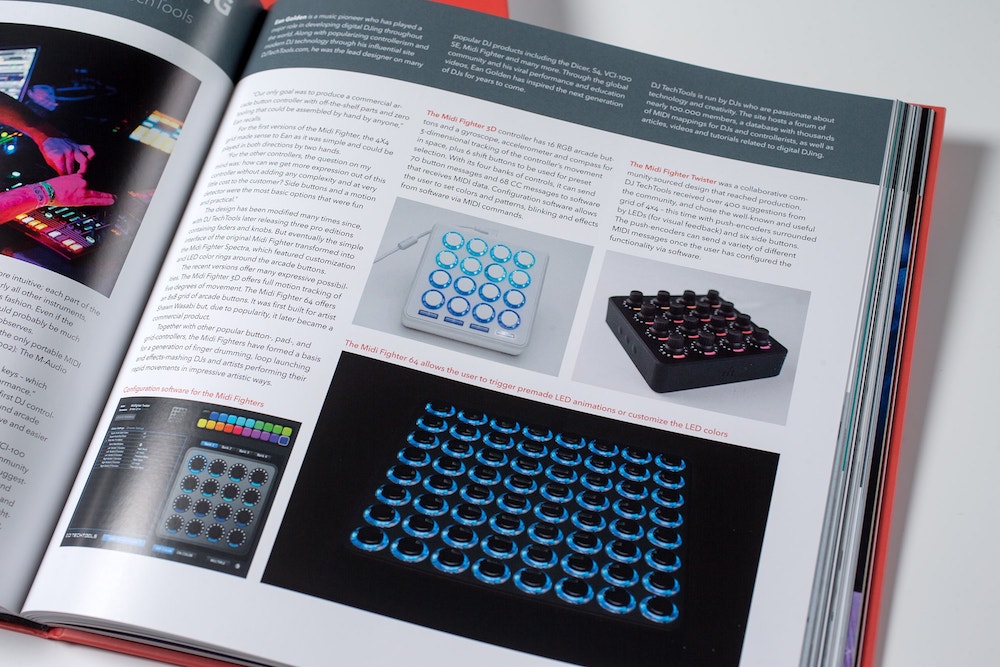

Wouldn’t you know it, the only interview in the book exclusively focused on DJing technology comes from DJ TechTools’ founder Ean Golden. He credits the helpful and accepting culture of the site’s community for helping to open up the formerly inclusive vibe of the DJ world. Ean’s arcade button and push-button encoder Midi Fighter controllers sprang from collaborations with members of that very community and exemplify the grid musical interface, where color-coding plays an important organizational role.

“Collaborative iteration of instruments is a key element, as it’s the only way that we, over time, can achieve a true instrument that is fine-tuned to the player.” – Ean Golden

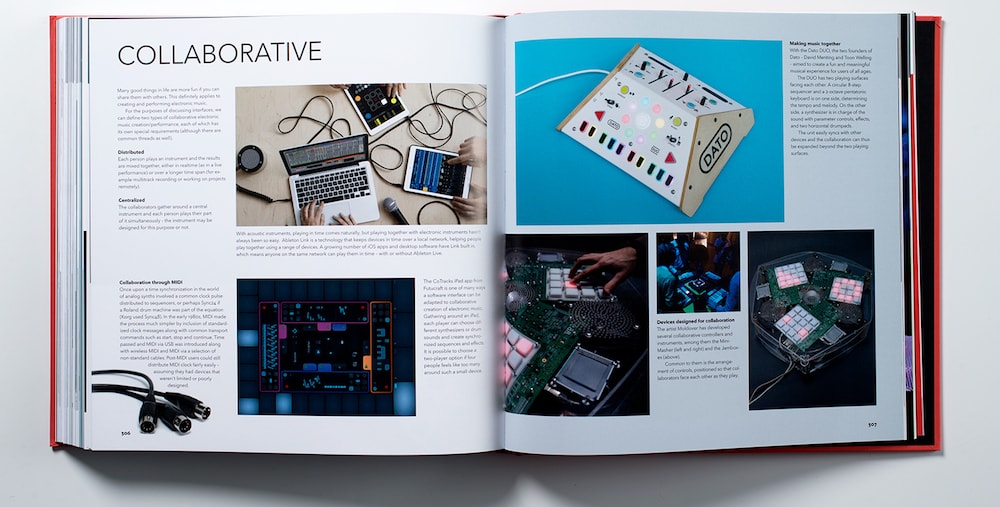

Push Turn Move’s final pages cover the emerging musical interface concepts, some of which have started to commercialize, while others simply provide a taste of what’s still to come. These include collaborative, multi-person inventions, as simple as the wireless syncing Ableton Link protocol and as complex as art installations where several inexperienced people can sit facing each other and jam out on pre-configured keyboards and other controls.

There are also new advances in gestural interfaces, such as the mi.mu gloves. These performance-oriented gloves incorporate 17 highly-sensitive motion sensors, a button, and haptic feedback in each glove, and are connected wirelessly for sending OSC or MIDI messages to the Glover software. This system lets users design their own actions and determine what those actions do in their software. They can instantly change mappings so that any gesture can have a different result.

“There are so many types of sounds or effects that don’t have a physical presence. They are software, hidden inside a computer… It’s these unsung heroes being brought out of hiding, that are alive and well in the studio but hard to unleash on stage… We have these incredibly expressive bodies, yet making and playing music can often find us hunched over a desk.” – Imogen Heap, Grammy-winning artist and mi.mu glove team member

Finally, the book covers the music-making possibilities in virtual reality and mixed reality that are on the horizon. These include The Music Room, The EXA, and Block Rocking Beats, variations on playing musical instruments within VR; Soundscape VR for creating synth music with up to three people; and AliveInVR, a VR Ableton Live controller.

Behringer is also experimenting with using mixed reality headsets like the Microsoft Hololens for editing patches on its WiFi-enabled Deepmind synthesizers. But these examples only serve as harbingers for possible paradigm-shattering changes to music creation and performance yet to come.

“In the future, I think for sure it will be a combination of visual software and the hardware, like a holographic environment where you see the patches and interact with them physically.” – Suzanne Ciani, modular synthesis pioneer and composer

This Book Brought to You By You

While there are many design books and music gear books, Push Turn Move did not come out under the old-media system of publishing companies predicting what would make a profit. Music technology is relatively insignificant to most media companies in the world.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it had to come out in the era of crowdfunding, when a passionate person or group of people can take to the Internet with their labor of love and find their tribe of like-minded people to pre-order it.

Push Turn Move found 1,430 Kickstarter supporters in 55 countries, enough to shatter its fund-raising goal, but not nearly enough for most book publishers to consider worldwide distribution. Several of the cutting-edge instruments in the book’s user-configurable controller and hexagonal key sections also got their start on crowdfunding sites, and this might inspire some to pursue their own musical inventions. But you don’t need to be a designer to enjoy this elegant book – just a love for gear.