With the advent of “controllerism” and the meteoric rise of DJ software, some may assume that the art of turntablism is fading fast. Attendance at the large competitions continues to drop, and the 20-year-old art form appears to need a breath of fresh air. Ironically, it may just be digital technology that brings it. Software like Serato Scratch Live is making the bread and butter of turntablists — scratch records — more accessible to everyone and opening creative doors to exciting new ideas.

For years, having your own scratch record to manipulate was a luxury afforded to a precious few. The technology and techniques that went into a DMC-winning performance were shrouded in secrecy as each performer tried to one-up the next. These days, you don’t have to drop $100 on a dub plate or be a former DMC champion to make your scratch sentences and routines completely original. With digital vinyl technology, a decent DAW and some minor technical know-how, you can make your own personal scratch “record” in just a few hours.

ADVANCED RECORDINGS

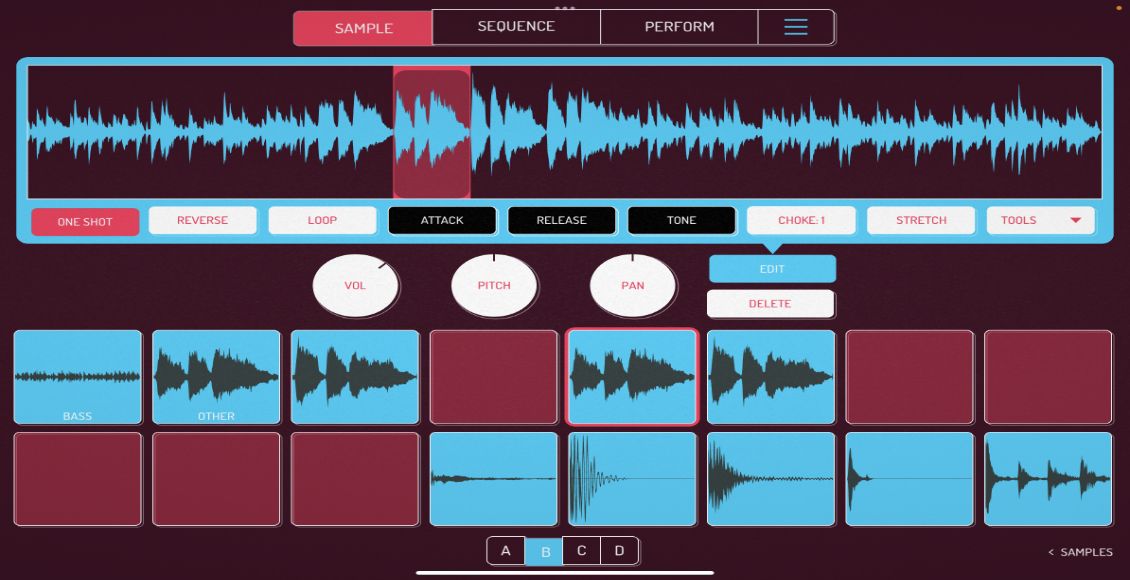

There are no magic tricks up Q-Bert’s sleeve; a scratch record is just a record — a series of samples recorded linearly on a record. The trick is just in how the samples are placed on the record. The speed of the drum loops and the spacing of the samples can create very helpful characteristics that make a crazy scratch sequence easier to execute. You may have heard people throw around terms such as “skipless records” or “Y record.” Those are common techniques used for creatively spacing samples around a record, which you can recreate in your DAW.

SKIP LESS

Relative mode in digital vinyl control systems like Scratch Live brought about the only true skipless-record technology. Skipless scratch records most certainly skip, but when you accidentally or intentionally move the needle you won’t lose the beat. That is because the makers of the records have taken into account the time it takes the needle to travel in one full rotation around the groove. At 33 rpm, it takes the needle 1.8 seconds, and at 45 rpm, it takes 1.33 seconds to complete the circle. So if a loop pressed on the record is always 1.8 seconds long, then each part of the loop will always fall on the same part of the record. Moving the needle around will make a skipping sound, but the loop will always fall back in the groove. What is the point, you may ask — doesn’t Relative mode accomplish the same thing? Yes, but it’s the creative application of this simple concept that has made many a turntablist’s show.

One common technique is to set up a series of loops that are all cut at the same bpm and loop several of them together. With this method, you can switch between drum loops just by moving the needle. Another technique is to loop a series of rising bass lines or tones so you can physically “play” the samples by moving the needle up or down the record. To accomplish that in your DAW, you just need to have a few figures handy. At 33 rpm, a few common bpms will always work, including 100, 133.33 and 166.66, which are 0.6, 0.45 and 0.36 seconds long, respectively. Because those lengths are all perfect divisions of the record groove length, they should provide a skipless groove. At 45 rpm, you have a few other options, including 90, 135 and 180 bpm, which are 0.66, 0.44 and 0.33 seconds long, respectively. Do you see the pattern? All of those bpms are perfect divisions of the length of one complete groove. If you create your scratch groove at 45 rpm, you can do a cool trick by alternating between 90 and 180 bpm loops, smoothly switching between hip-hop and drum ‘n’ bass rhythms just by lifting up the needle.

THREE-PART SHOW

The Y record was a concept that famed DMC champ Q-Bert introduced to the world in 2004. The idea is an expansion on the skipless groove concept, but instead of loops, samples are arranged in a specific pattern. Most Y records are cut using three samples spaced evenly across the record. At 33 rpm, you just need to create a loop that is 1.8 seconds long. Place the first sample at 0, the second at 0.6 seconds and the third at 1.2 seconds. With that configuration, the samples will always be at the same place on the record, at approximately 12, 4 and 8 o’clock. Loop that series for a while and then change the samples. Repeat for the duration of the record length. That way, you have the best of both worlds: skipless scratch samples and the ability to quickly move to new samples by just moving the needle. Q-Bert’s record employed a simple system of sample management that you may also want to try. Each of the three samples is always a different type. For instance, the first sample could always be a vocal and the second a drum hit. By keeping your sample layout consistent, you will always find the drums, vocals and effects on specific parts of the record.

Many of these techniques can be easily duplicated and in some cases performed more accurately with creative uses of loops and cue-point triggers. That does not mean the easiest road is necessarily the most rewarding. Finding interesting ways of performing complicated techniques with simple tools like the turntable can help the audience understand what you are doing and create a more interesting performance. In the long run, that might lead to more gigs and an enjoyable DJ career. Remember, though, it’s not what you use, but how you use it. So don’t let your medium speak more loudly than your art.