In today’s article, follow an all-too-familiar tale: a new DJ’s promo mix, uploaded to Soundcloud, resulted in a copyright strike. Instead of ignoring it, guest contributor Elizabeth de Moya decided to dig into the current state of Soundcloud’s content recognition system – and how takedowns like these really work.

From Beginner DJ Mix To Copyright Strike

After a long foray into college radio and music journalism, I recently purchased a Pioneer DDJ-SB2 DJ controller, and the basic version of Serato DJ (with plans to upgrade later).

My idea was to start club DJing. I didn’t need a lot of production equipment to seamlessly blend music. I’m not an event promoter or nightclub manager, but the idea of making people dance and have a good time at the club was appealing. My acquaintance, a music director at a nightclub, suggested I start sending out mixes to promote myself more.

Recently I posted a DJ set on SoundCloud, full of dubstep and trap remixes of popular hip hop songs circa 2005 to 2015. It was a play on the “retro dance party” theme that a lot of clubs throw. It’s also older tracks – ones that a club DJ is “supposed to play” during an opening set, except the bangers.

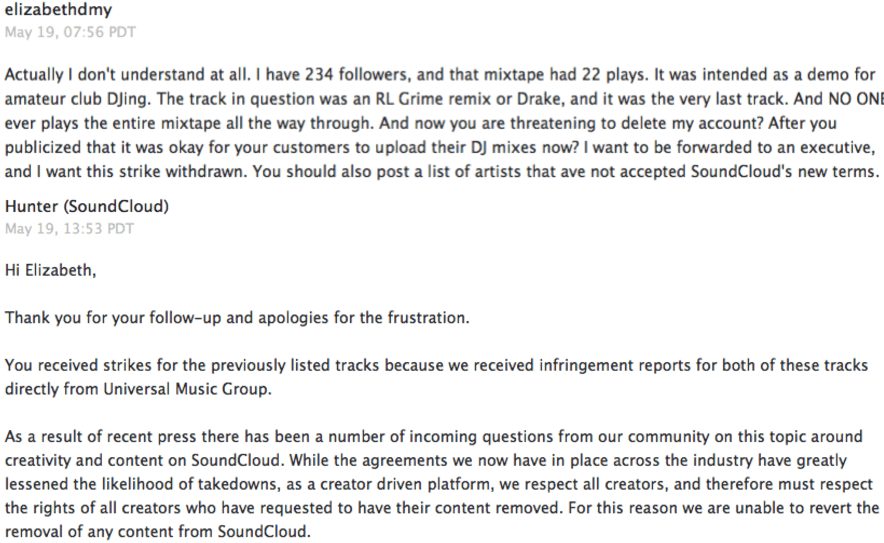

About two weeks passed when I received an email from SoundCloud informing me my mix had been taken down. Allegedly, I infringed Universal Music Groups’ (UMG) copy rights when I included “Club Paradise” (RL Grime Remix) by Drake as the last song in an hour long mix. My club demo had received just 22 plays. I have a little over 200 followers on the platform.

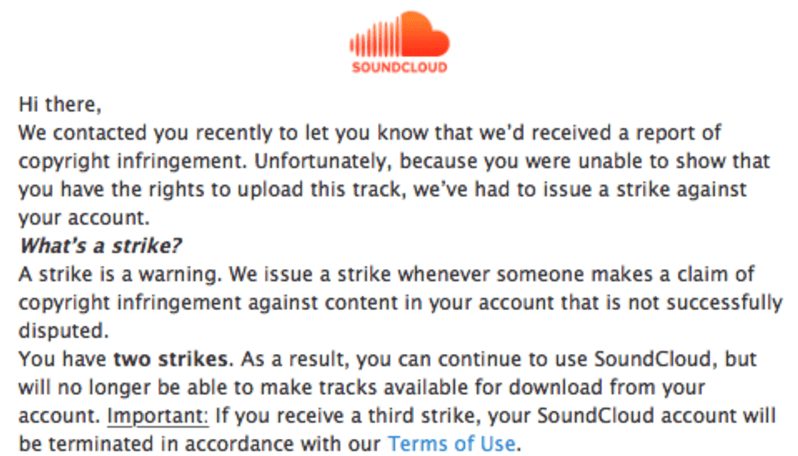

A few days later I got another message saying that a strike had been issued against my account. If it happened a third time, my profile would be deleted from SoundCloud. It felt excessive – especially considering claims made by SoundCloud’s co-founder/CTO in a press release in 2016 – stating that they were now allowing DJ mixes:

“During the negotiations for SoundCloud Go, we achieved agreement with collecting societies like GEMA in Germany, making these problems a thing of the past – even for users who do not subscribe […] This means that DJ mixes are now legal and problem-free on SoundCloud. So this is a very positive news for DJs. Furthermore, mixes should not be interrupted by advertising.” – Eric Wahlforss (Translated from German)

Shortly afterwards SoundCloud representatives amended this statement, because some artists had not agreed to their new terms. But they never told anyone who these mystery musicians were, leaving everyone to infer somehow.

Who Doesn’t Like DJ Mixes?

Who doesn’t like SoundCloud? What artist doesn’t want their music promoted by DJs? It might be a handful of famous people because no indie artist would oppose a music streaming platform that publicizes their music. Right? (I address this in a following section.)

Clearly Drake(‘s legal team) hasn’t subscribed to SoundCloud’s new terms, possibly because he is a very popular choice for remix artists who give away all his tracks. Taylor Swift would probably not allow bootleg mixes if she does not approve of Spotify. And of course there are a lot of old school artists that haven’t joined the digital streaming era because the format is still unfamiliar. Prince’s estate still won’t allow streaming versions of his music on Spotify or YouTube!

It would be simple enough to post a list of the artists that violate SoundCloud’s terms. But apparently they would rather delete everyone’s account and send out a lot of frustrating replies to emails. I would have taken the track down if they had just asked. I can make another mixtape.

I reached out to Drake’s legal representation at OVO Sound, but they have not responded.

Basic Copyright Law for Music

Of course, there’s a legal reason the mix tape was taken off SoundCloud but is still acceptable on Mixcloud. It all comes down to licensing rights and what platforms actually do.

When an artist writes a new song, they own both the original composition and the recording. But to enforce any ownership claims they have to register the copyright in their country. Most musicians also sign a deal with a music publisher such as ASCAP, BMI, GMR, or SESAC. It is the music publisher’s job to enforce the artist’s legal rights to the music and maximize profit, in exchange for a portion of the proceeds.

If you wish to perform or broadcast a song in public, you’re technically required to obtain permission from the owner of the song. Many venues do this by obtaining licenses from all the applicable music publishers. This applies to anyone in the business of sharing music, including background music services, concert promoters, dance clubs, hotels, restaurants, radio stations, retail stores, television networks, yoga studios and websites.

“If your business plays music without obtaining the necessary advanced permission from copyright owners, you are in violation of U.S. Federal Law.” – GMR‘s website

Mixcloud Vs. SoundCloud

Mixcloud is an internet radio platform exclusively for streaming radio shows and DJ mixtapes. They have a blanket music licensing deal with music publishers across the world. This gives them permission to stream any song in a DJ set. This deal is also why you can’t rewind mixes, include more than three songs by the same artist, or upload singles to Mixcloud.

“Mixcloud is a user-generated platform for internet radio. In the US we have licenses in place with SoundExchange, ASCAP, BMI and SESAC. In the UK we work with PRS, and are transitioning from a PPL license to direct deals with labels.” – Mike Wooler, Mixcloud Content Manager

SoundCloud’s website states that they are “a platform for creators.” Artists upload their music to the website where it can be discovered, played, commented on, and shared by listeners. Their Terms and Conditions state that they’re a hosting website where users may only upload original content. It doesn’t specify anything about is SoundCloud’s agreements with music publishers.

Soundcloud’s Transition To Licensed Music Service?

Does SoundCloud actually have the right to stream bootleg remixes, mixtapes and podcasts? Many producers and DJs already do this every single day.

Last year, Future of Music Coalition (FOMC) write about how the announcement of SoundCloud Go was supposed to mark a transition from an unlicensed service to a licensed one. It was also supposed to bring in a stream of revenue for SoundCloud. According to the article, only “Premier Partners” are paid royalties for streams on SoundCloud, and those partners are by invite only. These include the three major labels as well as a handful of distributors.

Following that logic, UMG had nothing to do with my mixtape being taken down, because UMG signed a licensing agreement with SoundCloud in January 2016.

It was picked up by the site’s automatic content recognition technology provider Audible Magic, which determined that I had violated Drake’s copy rights because they don’t have a publishing agreement. There was other UMG music in that tape (they’re practically the Illuminati of music).

Also no, Drake does not hate DJ mixes – but his label does hate the unlicensed use of his music.

What’s A DJ To Do?

As of now the only option for DJs is to use a different platform. The problem is that SoundCloud gets the most organic plays. That is a click by a real person that was not the result of an advertisement. I actually prefer Mixcloud because the track lists are well formatted, and all the artists get credit. But no one is on Mixcloud playing random mixtapes, or not mine anyway.

What we have here is a music streaming platform that lets DJs upload songs, remixes and mixtapes — but only certain DJs, playing certain artists. They’re not willing to tell their customers which songs violate the terms of their agreement, or withdraw a strike unless you know someone at UMG. However, they are willing to terminate your account for uploading DJ mixes after they gave the DJ community the go ahead.

On May 30, Variety reported that Stephen Bryan, Chief Content Officer at SoundCloud, was stepping down. He was the fourth executive to resign in 2017, along with Marc Strigel, Chief Operations Officer, Markus Harder, Finance Director and Neil Miller, General Counsel.