There has been a great debate taking place in forums around the digital DJ web. What is the best way to mix songs while DJing: externally on an analog mixer or inside your DJ software? Many DJs — myself included — have always assumed that mixing on an analog hardware mixer is the best option if you have the choice. To put that subjective assumption to the test, DJ TechTools interviewed numerous experts in the industry, including audio engineers, software developers and mixer manufacturers to get down to the bottom of this important question.

THE BIG QUESTION

Let’s assume you have DJ software, such as Traktor, that lets you mix internally or externally. When mixing internally, all of the audio signals from the decks are summed inside of the software and then sent out to the sound card as a single master output. All level controls, EQ and any distortion happens in the digital world before being converted to analog. When mixing externally, each deck’s audio is routed to separate outputs of your sound card. These outputs then connect to a DJ mixer, where the summing happens on the mixer in the analog world.

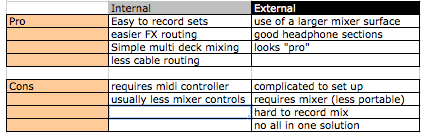

Before we dive into the audio quality question, each of these methods offers a few clear functional benefits.

At this stage, the contest is fairly evenly weighted with each option having clear pros and cons. The argument gets skewed when subjective experiences of audio quality start to get thrown in the mix. Statements like “external mixing sounds better” trump any pros/cons list, resulting in people making decisions based on assumptions rather than facts. So, to help us all understand the difference once and for all, we got in touch with the people who know this stuff inside and out.

THE ANALOG SIDE OF THE STORY

Our first stop in the analogue world is Rane, a Seattle based company known for making highly respected DJ mixers for more than 20 years. Rane makes analog mixers that sound good no matter how hard you push them, and digital mixers as well. That raises the question of how they get a TTM-57SL, which mixes all of the signals digitally on a DSP (just like software) to sound as good as their analog TTM-56. Steve Macatee, director of new product development, who has a lifetime of experience in designing quality DJ mixers, explains,

“Most people are used to the sound of CDs, which are 16 bits and 44Khz sample rate, but what we do in the TTM is far better than that. It’s a 24-bit world and 48khz sample rate, which increases the dynamic range and lowers the noise floor.”

A lower noise floor and wider dynamic range means that it’s much harder to distort a signal, providing the DJ with more head room. What happens when you do distort the audio though? Everyone is going to push the signal into the red at some point in the night, so isn’t that when analog starts to get more forgiving than digital?

Steve again corrected my assumptions,

“That’s not necessarily true. Because digital mixing technology has evolved over the past 20 years, you have digital converters that clip in very friendly ways. It really depends on the op amps and the circuitry you’re using. You can design an analog product where the audio clips the voltage rails and sounds like hell. [Editor’s note: think Pioneer DJM-500.] You can also design an analog summing buss that doesn’t clip and sounds pretty nice. Whether analog or digital, you can do a good job or a bad job of it. What really matters is the quality design of the summing circuits and the dynamic range you get on the output.”

Okay, so the quality of circuits really depends on the designer, but don’t analog mixers offer certain soft limiting features that keep a DJ mix sounding good even when they are pushed into the red? Not quite:

“That’s a fun question, because in the analog world, a lot of our DJ products have outputs stages with little fixed limiters that are trying to keep people happy and not make the signal sound horribly distorted when the DJ turns the sound full on. When you do the same thing in the digital world, you have a plethora of possibilities, because you can do things in a much fancier way without taking up crucial board space (inside an analog mixer) because now what you have is a software problem. The only limit is the amount of memory your DSP has, which limits how fancy of a limiter you can create and how the audio circuits are built.

So in reality, if you’re comparing apples to apples, then digital mixing has the potential to be more flexible and forgiving than analog… if it’s designed properly. Since each product is going to have different characteristics and qualities depending on how well they are made, you really need to use your ears and put both software and analog mixers to the test before judging.

DIGITAL MIXING

Traktor’s Take

We got Native Instrument’s take straight from none other than Stephan Schmitt, who created professional analog mixing consoles before founding NI.

We got Native Instrument’s take straight from none other than Stephan Schmitt, who created professional analog mixing consoles before founding NI.

“First of all, it is important to understand that audio summing circuits in a mixer or a similar hardware device are designed to combine electrical signals in the way of a very straightforward mathematical addition. In that sense, the internal mixing in Traktor – or any other properly designed audio software – is actually superior to a hardware mixer because it combines the audio signals in a mathematically precise way, and without introducing any noise.

One important aspect of digital summing is internal headroom, and this is where the audio quality can potentially suffer. Traktor overcomes this by using 32-bit floating point calculations, so headroom is practically unlimited (with 750 dB), and the mixer in the software can never produce unwanted clipping artifacts. This is not to be confused with the master output stage of the software that drives the audio interface — you need to take care not too overload this stage, and that’s why Traktor also offers an optional master limiter.

In a general you could call software mixing — or basic digital summing — “perfect” in terms of sound quality, and there is not even any DSP magic in the form of especially sophisticated algorithms required.

Obviously, certain analog mixers can color the sound in a way that some people find pleasant (though most mixers are much more likely to degrade the sound unless they have a really high-quality signal path). To cater for this aspect, Traktor offers the choice between a generic, “mathematically ideal” EQ on the one hand, and a selection of EQs emulated from actual high-quality hardware mixers on the other hand. These analog-modeling based EQs even color the sound in a subtle way when all bands are set at the zero position, in the same way as the analog counterparts.

When it comes to audio quality of DVS systems, the signal quality of the audio interface is a huge factor: the quality of the converters, signal-to-noise ratio and sheer output level. Also, software DSP functions such as digital effect algorithms and time-stretching do have a huge influence on sound quality, and require a lot of engineering effort and expertise. The difference in sophistication between a “standard” chorus or reverb algorithm and one that actually sounds good is enormous. Audio summing however is a very straightforward and comparably trivial part.

The Itch Side Story

What about the Serato camp and its relatively new Itch product? How are they doing summing in the digital domain?

“The Itch mixer is designed to have enough headroom to effectively mix songs together without hitting full scale at the output. Itch also has a master limiter on the main mix bus that will kick in if a DJ gains everything on full or is using high gain and lots of EQ, this limiter is to avoid clipping before being sent out to the sound card. We have a feature on the setup screen called overdrive where you can adjust how much headroom is available in the mixer before the output limiter kicks in. By default it’s set to it’s safest setting, which offers the cleanest sound. Some people like more limiting and a crunchier sound, so want this turned up. We also offer 6 or 12 DB boost on the EQs as an option, so a DJ can choose how they want it to sound.

STRAIGHT TALK

Equipment and software developers have a special expertise to be tapped, but their proclamations can also be biased toward the advantages of the particular gear they make. For some balance on this eternal debate, we turned to experts in the music technology education and journalism fields.

“Experience has indicated that analog summing is superior in creating separation and a better stereo image,” says Paul W. Hughes, a national manager at the SAE Institute chain of multimedia schools. “Tracks that have ‘a lot going on’ tend to lose definition when summing digitally in the box,” he continues. “Fundamentally, your [software] uses math and algorithms to blend the signals. That’s not how your ears process sound, so the more it has to sum, the more the sound will ‘feel’ as though it’s tanking out, losing punch, drive and energy. Pushing it louder will only result in distortion.”

George Petersen, the long-time editorial director of Mix Magazine and an active producer/engineer, says “Really, analog summing is the best way to go, but in most situations, the difference is pretty subtle.” Petersen doesn’t discourage anyone from mixing in the box, but he emphasizes the importance of a high-quality audio interface if you’re going to get the best sound using digital summing.

The quality of the digital-to-analog (D/A) conversion of your interface should be excellent, but so should the analog circuitry that amplifies the the sound after the D/A conversion. “Not only does the converter chip have it’s own sound,” Petersen says, “but the analog circuitry that’s built into a converter makes a huge difference on the sound, probably more so than the converter chip.”

Petersen cites cheap analog circuitry in an audio interface as contributing to the poor channel separation often associated with digital summing. While it’s not easy to verify the quality of the analog circuitry in an audio interface, looking at schematics can help. Petersen notes that low-cost interfaces will often follow the D/A converter chip with a stereo op amp, while his high-end gear follows the converter chip with two side-by-side mono amps on separate, non-touching circuit boards. “Are those cigarette pack-sized USB breakout boxes really treating the analog side of that signal properly?” Petersen asks. “Chance are usually no, they’re not.”

COMMON RESULTS

Everyone we asked had different opinions on the importance of summing circuits, but they all agreed on one important fact. The really critical part of sounding good when mixing with computers is the quality of the audio interface. If a sound card has poor D/A converters or poorly written drivers, then your software will sound bad. This is particularly important to remember as more and more DJs buy “all in one” controllers with built-in sound cards of sub-par quality. Wondering which sound card is right for you? Here are a few reviews of audio interfaces that we like, and another round up of “sound cards under $200” is on the way.

Native Instruments Audio 8 Review

Echo AudioFire4 Reviewed

Further Complications.

As if this discussion were not already complicated enough, a really interesting fact popped up during the course of our investigation. Which operating system you use can actually play a part in the the latency and performance of audio coming out of your computer. It turns out that the Macintosh native audio drivers are much better suited for high-quality mixing than the native Windows drivers. Expect a full article on this subject in the coming weeks.

THE BOTTOM LINE

It’s safe to say that there is no real audio quality benefit to mixing with analog mixers instead of in the computer. In fact digital mixing offers greater flexibility in dealing with distortion and soft limiting. Assuming that you have good software, a proper audio interface and the common sense to set them both up properly, you should be able to get a great-sounding mix either internally or externally. The real difference lies in each individual mixer and the quality of your audio interface.