Much of the basis behind the current state of DJing and electronic dance music came from the first generations of raves. Starting with a Roland TB-303 in Chicago, growing to undergrounds in the UK, and creating all manner of subgenres along the way, the story of the rave scene and the DJs who built it is fascinating. Check out the full story inside, including an exclusive interview with the father of acid house, DJ Pierre.

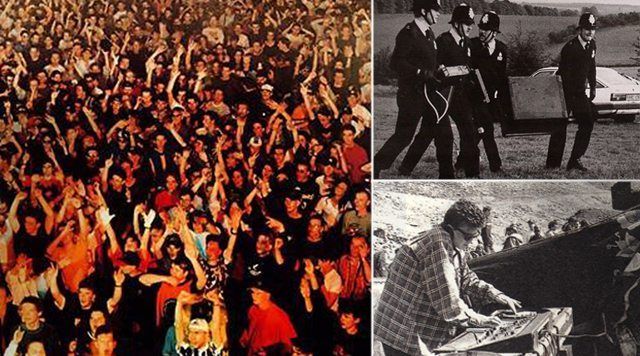

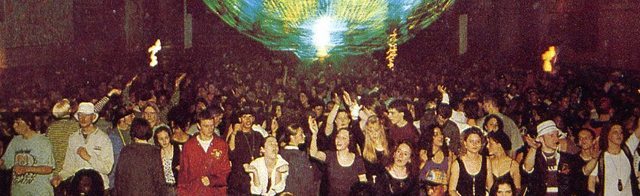

Raves began as an underground movement, where a group of like-minded people would get together and dance (in an enhanced state of consciousness) to all types of electronic music. Raves created a magical environment where people could dance for hours. Rave was founded on groundbreaking electronica and innovative DJs, but the scene encompassed more than just that. Laser lights, fashion and open-minded attitudes helped to build and spread the scene. It was only natural that a movement so magical would grow to epic proportions.

Rave: An all-night dance party filled with electronic dance music (techno, trance, drum and bass…)

Early Origins: Acid House Parties

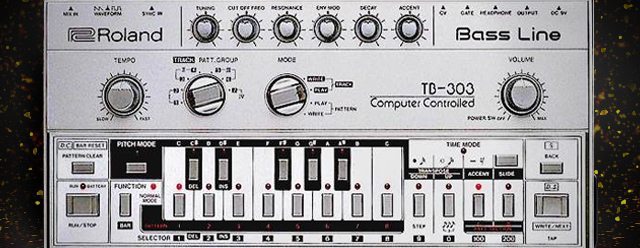

Chicago in the mid-to-late 1980s was the birth place of house music. After years of ‘jacking’ a new sound emerged: acid house. The sound of acid house was created on the Roland TB-303, a bass line generator. The machine could sculpt sounds using an array of buttons and switches. The company only produced 20,000 units and by 1985 could be found in second-hand shops for bargain prices. The young Nathan Jones (DJ Pierre) found one and used the 303 in an unconventional way to produce the squelchy sound of acid house.

This new sound began with a record produced by Phuture, a group founded by DJ Pierre, Earl “Spanky” Smith Jr., and Herbert “Herb J” Jackson. Newly turned on to the unique sounds of the TB-303, the trio released a demo of ‘Acid Tracks’.

DJ Ron Hardy played the track at the famous Chicago club Music Box; he reportedly once played it four times during a set before the crowd responded favorably. After numerous spins, it became a dance floor sensation. ‘Acid Tracks’ became the defining sound for the new acid house sound coming out of Chicago.

Our exclusive quick interview with DJ Pierre:

Where did you find the TB-303 that you produced ‘Acid Tracks’ on? What inspired you to create the legendary ‘acid house’ sound?

DJ Pierre: It found us! This machine had been around for years […] before we got to it no one actually tweaked the knobs and used it the way we did. It was created to simulate a bass guitar. It was not created to do what it did when we got a hold of it. I was at my homie Jasper G’s house and I heard a bass line and I wanted to know what machine he used to make the bassline. I loved the texture of it. I was excited when I heard it.

He showed it to me and there it was…the 303. I said to my friend Spanky, who is the other member of our group Phuture, “Yo…we have to get that!” He found it a second hand shop for 40 bucks.

Describe the acid house club scene in Chicago in the late 80’s – where were the parties, who were the DJs, what was the experience like?

DJ Pierre: The scene was created after Acid Trax was released. It didn’t exist before then. Other artists like Tyree Cooper, Fast Eddie, Armando and Marshall Jefferson followed up with classics of their own. Chicago is funny because there was not one particular scene for a style of house. House was just House and you heard everything mixed up in a DJ set. [..] The scene took off in Europe and Acid House is credited for the start of the rave scene in London. It was so big and filled with so much energy that the Queen herself called acid house by name and banned it.

What DJ equipment was used during sets in the late 80’s? Did DJs use any other gear in their sets?

DJ Pierre: Drum machines like 808s and 909s and of course 1200s were used for vinyl. We would use GLI and Urei mixers as well.

What are some other important acid house tracks (from the 1980’s) that we should all listen to?

DJ Pierre: “Acid Trax” because it is the beginning. “151” by Armando. “Land of Confusion” by Armando. “We Are Phuture” by PHUTURE.

How did acid house impact the rest of the rave scene that followed?

DJ Pierre: It gave birth to it. Because of the excitement and ‘high” at these acid house parties, the UK banned them. […] So you know how it is, if mainstream says “no!” then the general youth consciousness says “yes”! It went underground. The underground rave scene and secret parties paved the way for the commercial rave scene you see today. Acid house was behind that and the UK played a huge role.

Any advice for new school DJs and producers from your experience developing the acid house scene?

DJ Pierre: I always say study the history of the music you produce now. [..] In general, study the creators and founders. Studying the origin will give you a richer, more vibrant meaningful outcome. […] You will be inspired by listening to what came before to create your own vibe and feel.

In the late 1980s, Chicago’s house scene suffered a crackdown on events by the police. One of the only radio stations in Chicago, WBMX closed down, which meant house records were no longer heard on the radio. As a result, record sales began to slow down. However, the house and acid house scene was just starting to take off in the UK.

London House Scene (Mid-late 1980s)

By 1987, house music was in full swing in the UK – tracks like Steve “Silk” Hurley’s “Jack Your Body” had climbed to the top of the charts. Acid house hadn’t really made a big impact, until a group of four DJs (Paul Oakenfold, Danny Rampling, Nicky Holloway and Johnny Walker) took a trip to Ibiza to visit the acclaimed club Amnesia. They heard the resident DJ Alfredo blending records in the ‘balearic’ style, which fused together funk, soul, dance and a few Chicago acid tracks.

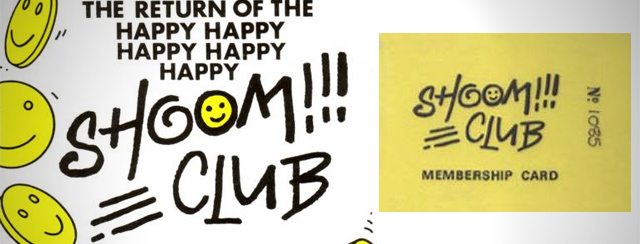

When Danny returned to the UK, he threw an event to bring the spirit of Ibiza to the UK. ‘Shoom’ was held on December 5, 1987 in a fitness center in on Southwark Street. The party went all night; acid house blared on a sound-system provided by Carl Cox, and the crowd raved on the then-new drug ecstasy.

I supplied the sound system for the first two Shoom club nights. Danny asked me to come down because he knew I was already into the music.[…] This whole rare groove movement had lasted for years in London but it couldn’t really go any further, whereas house music pointed the way forward. – Carl Cox

The third Shoom flyer featured the smiley face that became the defining symbol of acid house. This period became known as the Second Summer of Love, a peaceful movement that similar to the Summer of Love in San Francisco.

It was all one love, everyone together. Anyone can dance all of a sudden, freedom of expression. Dress down, not up. Converse trainers, smiley T-shirts – a sort of tribalism took over. Everyone was happy to be the same. – Pete Tong

Nicky Holloway opened The Trip in London’s West End; the club heavily played acid house, and stayed open until 3 am. Party go-ers would spill out on the streets as the nights ended, which attracted police attention. These bursts of late night activity may have encouraged the UK’s strong anti-club laws, which made it difficult for promoters to put on events in clubs. As laws became more rigid, groups began to gather to dance inside warehouses and secret locations – early raves.

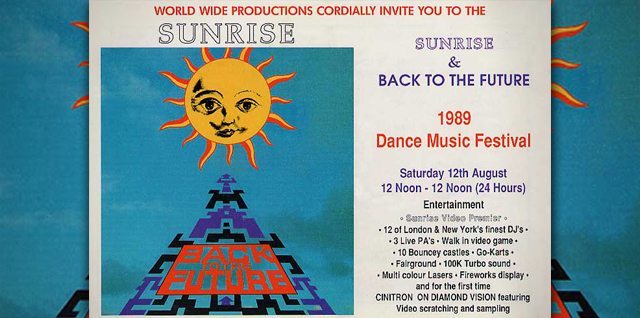

Organized by production companies, raves began to gain press attention. A popular fanzine called Boy’s Own was responsible for publishing the first article on acid house (written by Paul Oakenfold). Boy’s Own also held the first documented outdoor acid rave in 1988 (legend has it that a teenaged Norman Cook – aka Fatboy Slim – was turned onto house music during one of their parties).

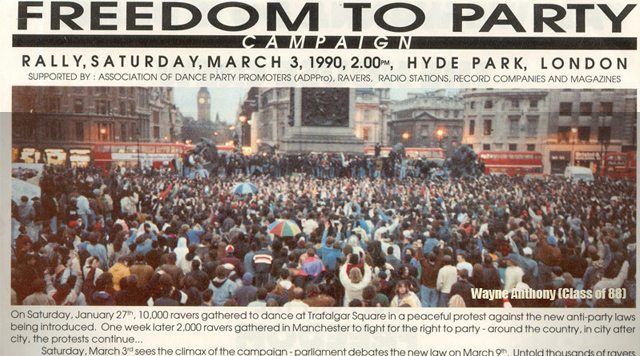

Promotion groups Sunrise and Revolution in Progress (RIP) began to hold bigger events. Sunrise transformed the underground movement into large-scale dance events. The crew organized a massive campaign in Trafalgar Square called Freedom to Party, which eventually led to a change in the UK’s licensing laws, and venues were given the go-ahead to stay open all night.

There was quite a bit of reported psychedelic and club drug use at these all night events, which gave rise to negative media attention. Acid house was banned from radio, television and media outlets, but during the backlash, a credible UK acid house record managed to break into the mainstream. Produced by a mysterious artist called Humanoid, ‘Stakker Humanoid’ reached #17 on the UK charts in 1988.

Cuts from the Era:

Genre Creation in the United Kingdom (1990s)

By the early 1990s, it became more challenging for promoters to organize one-off events. New bylaws were passed in an attempt to discourage promoters from holding raves. Despite this, organizations such as Fantazia, Universe, N.A.S.A. (Nice and Safe Attitude), Raindance, Amnesia House, ESP, and Helter Skelter were holding large-scale legal raves in warehouses and fields.

Around the same time, new musical styles including jungle and happy hardcore began to emerge. The scene began to divide as it became difficult to set up parties with multiple rooms for different genres.

In May 1992, the government in the UK passed a bill that focused on electronic dance music and raves. It gave police the right to stop open air parties, two or more promoters who were organizing raves, and people on their way to raves. After 1993, most raves took place in licensed venues, including Helter Skelter, Life at Bowlers, the Edge, The Sanctuary, and Club Kinetic.

Around the same time, drum and bass was born from a fusion of hardcore, house and techno. It originated in the breakbeat hardcore sector of the UK’s acid house scene. Both DnB and jungle featured breakbeats played over fast 4/4 dance beats. Records like The Prodigy’s ‘Jericho’, Rebel MC ‘The Wickest Sound’ and A Guy Called Gerald ‘Anything’ (below) helped to shape the sound that would become drum and bass:

A selection of the hardcore tracks being produced had a light and upbeat style. In response to this, a group of producers began to focus more on darker sounds and darkcore, a style that influenced jungle was invented. Here’s an example of darkcore in Goldie’s classic ‘Terminator’:

The darker sound appealed to the reggae and dancehall community, and soon dub remixing techniques were incorporated into the sound, alongside samples from urban music. It was common for producers to cut apart loops to create increasingly complex breakbeats; the most popular break to sample from was the Amen Break.

Producers who quickly became popular included GrooveRider, LTJ Bukem, and Andy C. 1994 was the peak of jungle; this was the year jungle was most influenced by rasta vocals and ragga basslines. Rave promoters began taking note that jungle was gaining popularity, and created parties with names like “Jungle Mania” and “Fantazia takes You Into the Jungle”.

By 1995, a counter style to ragga jungle emerged, dubbed ‘intelligent’ drum and bass. The king of this scene was LTJ Bukem and his label, Good Looking. This new sound focused more on warm tones and atmospherics and was a contrast to the aggressive ragga style. Fabio, Doc Scott, Grooverider, Photek and Dillinja were all active producers and DJs who pushed the new sound forward.

Roni Size, Krust and Dj Die might be considered the DJs who made Drum and Bass more mainstream – as well as Goldie. In 1995, Goldie released his masterpiece “Timeless” (below) which sold over 150,000 in UK alone.

The genre started entering the club scene, with DnB DJs beginning to get booked for house-oriented clubs. Ministry of Sound started to hold drum and bass sessions. Even as the sound continued to gain popularity in the mainstream, the writing was on the wall for the rave scene. An organization called World Dance put on their “last” rave at Lydd Airport. “Here is your last chance before another chapter in ‘Rave History’ comes to an end!” the adverts posted around London proclaimed.

1990s in the United States

One of the forefathers of the rave scene in the US is DJ Scotto. Inspired by the fabled club Hacienda in the UK, in 1992 he put on Manhattan’s first rave at the Studio 54 venue (then called the Ritz). The party featured (among others) DJ Frankie Bones, Rozalla and Moby performing live.

Frankie Bones would go on to start his own successful series of raves in Brooklyn, Storm Raves – where future international DJs like Josh Wink and Sven Väth got a chance to perform. Frankie also allegedly was the man behind the concept of PLUR, having once famously yelled on the microphone during a fight at a Storm Rave:

“If you don’t start showing some peace, love, and unity, I’ll break your faces.”

Many smaller promotional groups sprung up in the US, which caused a real ‘scene’ to develop, and Scotto’s NASA collective (Nocturnal Audio and Sensory Awakening) went on to produce rave tours that featured Moby, Prodigy, Orbital, Aphex Twin and then-emerging producer Richie Hawtin.

In the 1990s, one of the most prominent rave promotion crews was Global Underworld Network. They organized the OPIUM and NARNIA Festivals that drew an incredible attendance of over 60,000 people. Narnia was featured on MTV and twice in Life Magazine, and honored as the Event of the Year in 1995. Narnia became known as the “Woodstock of Generation X”.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Bay Area experienced a surge in popularity in rave culture. Small, underground parties began to take off, and expand from SF into the surrounding areas. With no curfew in place, venues would have up to 20,000 people partying every weekend. By 1991, raves were exploding, and flyers could be found up and down Haight Street. ‘Homebase’, and ’85 & Baldwin’ were two of the biggest venues that raves were held at in the Bay Area – but raves also appeared in open air venues (watch three different SF area raves in the video below).

In LA, promoters Vince Bannon and Phil Blaine brought in acts like 808 State, Aphex Twin, Massive Attack and Prodigy to play. California became a notorious destination for raves in the United States. The world flocked to attend parties that took place there and listen to the internationally renowned DJs who played.

THE END OF THE RAVE ERA

As the rave scene grew globally, it gained prominent negative press in the mainstream media (watch this Fox News report from 1998) as a result of a few tragic incidences that happened, and the scene as a whole came to an end. Some participants in the scene did use illicit substances, but to many, a rave was more than staying up all night partying. It was about experiences: seeing a DJ you’ve always to see play, or even a special MC booked from overseas. Thousands of people all around the world flocked to raves every weekend.

The late 80s/90s were a golden era for DJs, and the rave scene helped electronic music emerge, grow, and hit the mainstream market. For all DJs, we highly recommend digging in the (now-virtual) crates to hear where the EDM music scene we have today came from, and how much/little has changed.

Editor’s Note: This article is just a small sample of the massive story of raves and electronic music – here’s a selection of links to check out to learn more: