It’s no secret that Berlin is largely regarded as the DJ capital of the world – a world where DJ-based nightlife flourishes without the holiday expense and overblown glitz of destinations like Ibiza and Las Vegas. But what can the rest of the world learn from the behavior and business of the DJs, producers, and audiences who make up this successful scene? Guest writer and sociologist Jan-Michael Kühn explores Berlin’s underground behaviors from a very academic lens in today’s article.

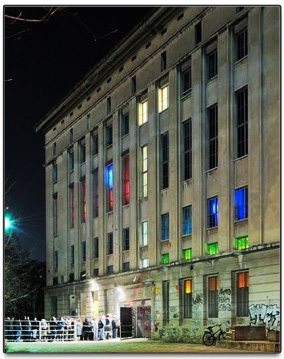

Header Photo Credit: Carolin Saage

Where Did Berlin’s Scene Come From?

Electronic Dance Music emerged in the USA—but it found a place to dwell and thrive in late 1980s Berlin. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Detroit’s aesthetically radical prototype mixed with the disused industrial spaces and dirty basements of East Berlin to define what we understand as club culture today. For many, Berlin’s techno scene is a benchmark for club-music culture. Numerous producers and DJs relocate to Berlin for the scene, and many techno fans travel to the city just to take in its world-renowned nightlife. No other city offers so many clubs, event organizers, and labels. New trends arise and are absorbed—and often ignored and laughed at: Techno in Berlin doesn’t necessarily define itself through innovation, but rather through distinctive and discerning taste.

Since emerging out of a cocktail of subcultural crowds, the work and business of techno and house music in the city has developed into an economic sector, a scene economy of its own. For some, spinning and producing tracks and throwing parties continue to be a hobby; but for many others, these pastimes and passions have turned into a form of gainful employment and a professional career.

Since emerging out of a cocktail of subcultural crowds, the work and business of techno and house music in the city has developed into an economic sector, a scene economy of its own. For some, spinning and producing tracks and throwing parties continue to be a hobby; but for many others, these pastimes and passions have turned into a form of gainful employment and a professional career.

Countless clubs (like Berghain, Watergate, Golden Gate, and Ritter Butzke) labels, agencies (for booking, promotion, and/or management), business firms (both vinyl and digital music production), media (scene zines, blogs, online forums), and distributors have cropped up around the musical practices of DJing, music-production, and event-promotion, providing the scene with its own infrastructure and economic supply chain.

Berlin, Capital City Of The Underground

One word keeps on popping up in conversation with the people that make up the local scene economy: underground. Although in everyday life nobody seems able to define this term precisely, you find it in use everywhere in this scene—especially where musical aesthetics come into play. Regardless of whether it’s about the music itself, the DJ’s abilities, the party or the location, “I prefer something more underground” is always the refrain. One of my interviewees, a label owner, put it succinctly:

“Berlin isn’t Lady Gaga or Paul van Dyk; this is the capital city of the underground.”

To put it very simply, this underground has four dimensions: modes of production, subcultural distinctions, internal hierarchies, and modes of consumption.

First, Berlin’s house and techno scene economies have particular ways of producing music that are remarkably different from how the commercial music industry operates. Second, these modes of production and the aesthetics of this musical subculture are symbolically differentiated from “mainstream” music production (thus also securing their survival) through opposition to concepts like “commercialization,” “selling out,” and “the masses.” Third, hierarchies develop within and between underground milieus, often implicitly based on social class, wealth, and other forms of privilege. Fourth, these scenes promote modes of listening and dancing that differ from what one associates with pop songs, concerts, and mainstream discotheques.

Techno For Techno’s Sake

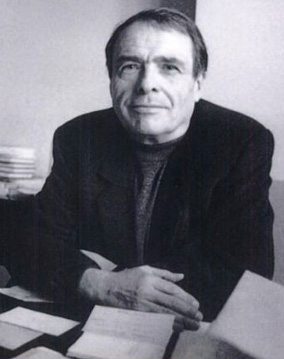

In his research on art appreciation, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu noticed a trend towards two poles with opposing cultural logics.

- The “autonomous pole” defined itself by its cultural orientation, in which the furthering of art itself took highest priority over any political, moral, or economic interest: art for art’s sake, as the saying goes.

- The other pole had a commercial orientation, treating art as just another form of commerce like any other, in which art is produced based on its marketability.

Each pole had its way of making value and profiting from it, but they are also in tension with each other.

This tension exists in electronic dance music: on the “autonomous” side you find scene-based dance music with roots in Detroit, New York, and Chicago, along with the club/open-air party culture of Berlin; on the other side you find mass-produced and profit-driven “dance pop,” which readily absorbs any style that promises to increase record sales. Both poles have very different definitions of success, as well as sharply divergent aesthetics and modes of production.

Making Music to Get By: Subcultural Music Scenes

Music scenes are entities in which people can freely assemble and form communities around the aesthetics of a particular music culture.

For techno and house music scenes, involvement starts with a random visit to a club or first listening to recorded DJ sets. A few will become passionate about the music and the clubbing experience, visiting clubs and other events with increasing regularity. Although this participation may be rather passive at first, it quickly becomes more active. Many will begin to seek out certain sub-genres, follow certain DJs, develop expert knowledge about the scene, its clubs, do’s and don’ts, local artists, and so on.

Some scenesters start to DJ, throw parties, launch music labels, build scene-related businesses, or simply find work at clubs, labels, and agencies. At this point, they’ve begun to combine their passion for a certain aesthetic with commercial interests. This might remain a hobby for some, but this soon becomes a profession and a business for others. Nonetheless, this business orientation usually is limited by the cultural values and institutions of the music scene.

Notably, these producers don’t start making whatever musical style is most profitable at the moment. They consciously miss opportunities to make more money, because the feelings of enjoyment and freedom they get from their favorite music is more important to them. They see “earning a living” as being able to get by instead of pure profit-maximization. That is, they reconcile their professional and economic interests with their desire for self-determination and artistic freedom by aiming for financial survival and social security. For them, money exists to make their lives and their artistic activities possible, not the other way around.

The small-business structure of many of the scene’s entrepreneurs encourages this logic, since it places fewer practical constraints on an individual than a large organization with numerous employees. Also, coworkers at clubs and labels usually share their passion for this music, and so there is often an intimate, “family” atmosphere in these organizations. As a result of all of these factors, underground music scenes develop economies where personal aesthetics, individualist ethos, and alternative economic goals go hand-in-hand.

By contrast, major music labels (and larger “indie” labels) operate very differently: music is first and foremost a business, and the decision-makers at these labels aim to sell as many recordings as possible to the widest possible audience, regardless of what that music is. Their high costs make it necessary for them to focus only on music with “mass appeal.”

“That’s Too Commercial For Me”

Stemming from a deep and personal investment in their music, many scene members maintain very exclusive and anti-mainstream views. Nowadays culture has a tendency to overflow its boundaries, and so does subculture. As “mainstream” EDM has become increasingly popular and successful, many scene insiders have felt the need to openly reject this trend as “fake” or “inappropriate.” This rejection entails aesthetic and social exclusions, such as refusing to book DJs who play music associated with this trend or trying to exclude clubbers that would be into this kind of music.

These exclusive subcultural orientations have become a way to make sense of the cultural landscape, drawing boundaries around “our” aesthetics and “our” modes of production. It’s a form of resistance to mainstream culture that is primarily rooted in aesthetics, rather than class or counterculture. In most cases, these subcultural distinctions are a reaction to the perceived corruption of “culture” or “art” by monetary interests, exemplified by large-scale music events and personified by multinational media conglomerates and their “lifestyle marketing.”

Familiar Atmospheres vs. The Masses

Another way that scene members differentiate themselves from the teeming masses is by their preference for the familiar (in the sense of “intimate”).This term describes the warm, intimate atmosphere that one typically finds at events with between 100 and 1500 people, in which attendees have a heightened sense of personal connection with others.

Within underground club scenes, there is a strong preference to be among other clubbers that share certain characteristics (like shared interests, but also shared social background – class, age, education, etc), are long-time participants in the scene, and who have a lot of overlap in their social networks. Mainstream discotheques and mass street festivals stand in as counter-examples of “familiar” club scenes: random and undefined masses of humanity, young and old, dancing to the popular products of the music industry, taken from the “best of the 70s, 80s, and 90s” charts of radio and television.

Too Young, Too Old, Too Many Hipsters, Too Working-Class

Berlin scenesters go on enthusiastically about how little social inequalities matter to the scene, but various studies have shown the opposite: age, gender, ethnicity, various other groupings have a fundamental impact on music scenes. Moreover, there are correlations between the “cultural capital” one inherits from parents (and accumulates through a lifetime of education) and one’s choice of preference for music clubs or discotheques, including how one dresses and grooms oneself. In short: people with a higher level of education tend to visit more private, smaller, and more familiar locations like music clubs, whereas people with less education are more likely to attend open festivals and parades.

This has a direct impact on the economy of Berlin’s house and techno scenes. Party promoters, for example, will first organize parties according to their tastes, personal interests, and social backgrounds. The promoter strives to attract a certain crowd with a certain demographic makeup that is attractive to the promoters but also other clientele. Over time, this develops into a series of parties associated with a particular image—and the composition of the crowd is a very important part of that image. Maintaining and developing this crowd becomes essential to financial success, as clubbers will stop attending if they feel that the crowd has somehow gotten “worse” or “random.”

People will very often refer to certain groups of people, complaining that the crowd has become “too working class,” too “hipster,” “too many students,” and so on. In order to preserve the party’s “brand,” a doorperson becomes an economic necessity, in order to ensure the appropriate mix of people inside the club. Explicit exclusions based on supposed social-structural characteristics are hard to detect. And so, this “underground atmosphere” emerges out of a vague form of exclusivity, where some people can’t get in for elusive reasons. At the same time, the almost magic feeling of being “chosen” grants those who get in a sense of personal validation and belonging.

Producing Tracks, Mixing Sets

One final aspect that merits attention here is the relevance of the scene’s own cultural forms and practices. These play an important role in sustaining underground, subcultural identities.

Techno and house music differ in many ways from other styles of popular music. Instead of songs by bands or songwriters, designed to be played on the radio, TV, concert halls and mainstream discos, underground music producers create tracks that are intended to be seamlessly mixed by DJs into their sets, played in music clubs over high-capacity sound systems. This track-based unique mode of performance, listening, and dancing places the club in the center of this music scene and has historically differentiated itself from song-based popular music.

Jan-Michael Kühn is a doctoral candidate in sociology (Technical University Berlin), currently writing his dissertation on the scene-economy of the Berlin techno scene. He also DJs as DJ Fresh Meat in Berlin’s nightclubs and manages the Blog, Berlin Mitte Institut for Better Electronic Music. Translation by Luis-Manuel Garcia.