Remixes and re-edits/edits have been an integral part of dance music culture since the early days of Disco. In today’s article, guest contributor Harold Heath looks at the history of the Re-Edit and the Remix and examines what defines them.

Remixes, edits, re-edits, reworks, mash-ups, dub mixes, bootlegs – dance music can be a confusing place. Take two successful original tracks of recent years, DJ Koze’s ‘Pick Up’ (above) and Midland’s ‘Final Credits’ (below). Both tracks contain substantial samples – we’ve put the original tracks below the edits (from Melba Moore and Lee Alfred, respectively). The sample usage in both suggest they could almost be called re-edits. However, the additional original production and arrangement completely changed the source material to create something exciting and new.

Are they original compositions, remixes, re-edits, or even reworks?

This question can be tricky to answer. The boundaries between remixes and re-edits have become blurred over the last few years, and there’s never really been a clear dividing line. However, there are a couple of main features which define remixes versus re-edits. One is about legality and one relates to how they were produced.

Production of A Remix vs Re-Edit

First up, let’s discuss the production of these two types of tracks. A remix is when a producer has access to the original recordings from a song, including the separate audio tracks, enabling them to either treat or entirely replace parts in isolation – like the bass line or the percussion.

A re-edit, on the other hand, is made from the finished full recording of a song rather than the individual audio parts. This vastly reduces the creative licence available to a producer. They can’t replace the bass or put effects on just the vocal as they only have the entire song to play with. Instead, edits are about re-arrangement with the aim of making a record more dancefloor friendly. Common things to do when making a re-edit include:

- cutting and pasting parts

- extending intros and breakdowns

- removing some sections, shrinking or elongating others

Why Did DJs Start Making Re-Edits / Remixes?

Why was creating this type of edit or remix even necessary? Peter Shapiro, in his seminal book about the roots of disco, ‘Turn The Beat Around‘, puts it simply;

“DJs always wanted longer records with longer percussive passages.”

Francis Grasso, DJing at the Sanctuary in New York in the early 70s, had discovered that percussion-heavy records and breaks (when the instruments drop out leaving just the drums) were phenomenally effective on the dance floor. DJs like David Mancuso and the pioneers who followed (like Nicky Siano, Bobby DJ, Steve D’Acquisto; and later Walter Gibbons, Frankie Knuckles and Larry Levan) all sought out longer records with percussive breaks and vamps (repetitive instrumental sections – they pre-dated the loops of house and techno).

Hip Hop DJs had also observed the irresistible power of the break on dancers too. They all knew that longer records really allowed a crowd to ‘dig in’, to really get into their groove and lose themselves in the music. All sought out longer tracks, digging into obscure album cuts and rare imports to acquire the sort of records they desired, knowing they could use breaks and vamps to segue smoothly from one track to the next, keeping their audience locked in on the dance floor in the process. And if the record they were playing didn’t have a long break or a long vamp, they could create one by mixing between two copies of the track.

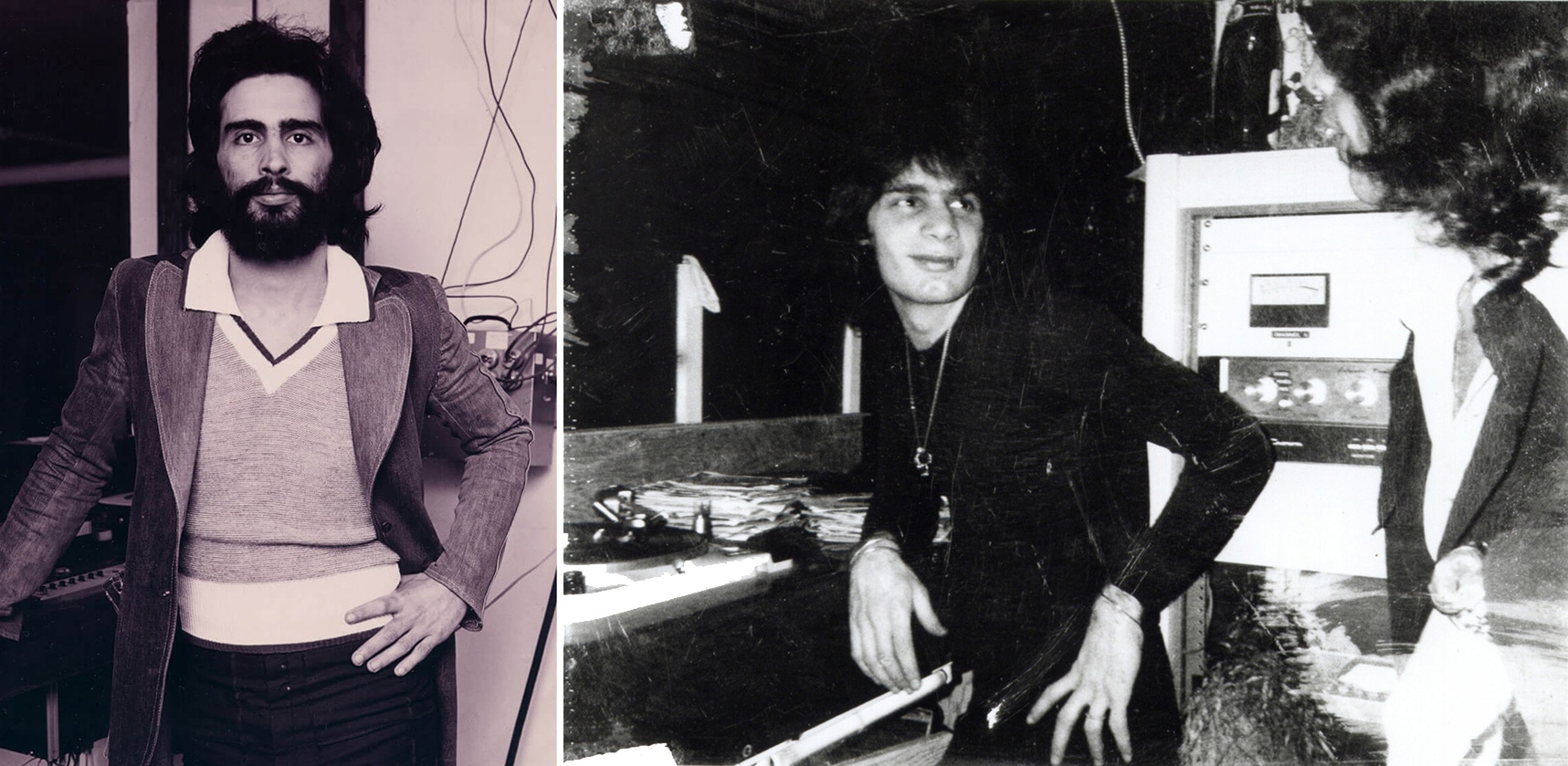

It is this collective discovery, this secret DJ knowledge, that drove the invention of both the remix and the re-edit in the 1970s. DJs from both the disco and hip-hop worlds would use two copies of the same tune to extend breaks and vamps and to eliminate interruptions to the musical flow. The sole purpose was simple: they never wanted to give anyone an excuse to leave the dance floor. DJs began making their own reel-to-reel edits to mimic this process, to create long, danceable grooves. Edits were often simply neater cut and paste versions of what they would do live with two records. The remix too was born from the same necessity: DJs needed and dancers wanted records that were specifically re-tooled for the dance floor.

The Legality Of Remixes vs. Re-Edits

The second classically defining feature of remixes and re-edits was legality. Remixes were generally done ‘officially’ – commissioned by record labels and perfectly legal. Re-edits were done privately, usually for use only by the DJ who made them and legally, were in a much murkier area. Although technically infringing copyright, throughout the pre-digital era the larger music industry was content to ignore DJ re-edits as they could be an effective promotional tool for the record labels and it was only working DJs who had access to them.

However, recent years have seen a sharp rise in re-edits being released and sold as either original compositions or as ‘reworks’. There are huge quantities of unlicensed re-edits, remixes, cover versions and mash-ups online. The major labels no longer turn a blind eye to producers using their clients’ work uncredited, and all the majors have entire departments dedicated to tracking down sample infringements and safeguarding any potential royalties for their rights holders. This only becomes an issue for you if your Love Is The Message re-edit on SoundCloud suddenly becomes successful and you’ve not cleared the sample: then the lawyers will come looking for you.

The Already Fuzzy Line Keeps Blurring

So is there a clear answer to the question of difference between remixes and a re-edits? Access to the original parts still makes something a guaranteed remix, but it’s not a requirement anymore. You no longer need original parts to make a final production that sounds more like a remix. Software like Logic, Ableton Live, and Reason have become more sophisticated, and enabled producers to substantially manipulate and change the source material. There’s a whole competition dedicated to audio signal separation that could end up in future DJ software, and programs like Xtrax Stems (read our review here) already does its best to split up tracks into stems.

https://soundcloud.com/dr-packer/love-come-down-dr-packer-rework-1

Artists like DJ Koze, Midland, Rayko, Late Night Tuff Guy, Dimitri From Paris and others continue to produce quality new club tracks based on reinterpreting old music, each with quite different approaches and results, from the Glitterbox bangers of Dr Packer (above) to the sublime underground disco-tech of Psychemagik (below).

Re-edits have been as important in the development of dance music as remixes, and many of our favorite tunes are simply reinterpretations of older music, whether through a 2 bar sample loop or a new rework of an entire song; dance music has always greedily cannibalized its past.

If we’re looking for a clear, simple definition, then the original definition still stands, even if the boundaries are sometimes a little blurred. A remix is a new interpretation created from the individual parts of a song, whereas a re-edit is created from the entire song. And until someone comes up with a better idea, when it comes to anything that doesn’t neatly fit into either category, we’re just using the term ‘re-work’. Simple!