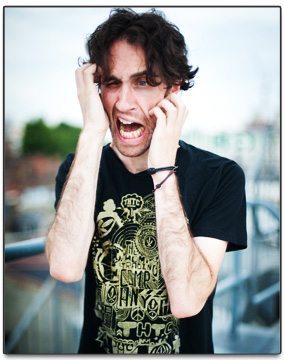

Today we’re bringing you an in-depth interview with none other than one of the modern living masters of live performance and looping, Beardyman. Over the past few months, he’s been building a brand new live performance setup. While many of the details remain top secret, the man himself shares how he’s evolved from a simple guitar loop setup to the new custom-designed Bearytron 5000 mkII – read on for the full story!

Few musicians dream up ideas that push into uncharted territory. When they do, they aren’t necessarily making better music than songwriters writing catchy-but-been-done-before pop hits. But true innovators that move music and technology forward are doing something with more profound consequences.

Few musicians dream up ideas that push into uncharted territory. When they do, they aren’t necessarily making better music than songwriters writing catchy-but-been-done-before pop hits. But true innovators that move music and technology forward are doing something with more profound consequences.

What beatboxer/live-production performer Beardyman (aka Darren Foreman) dreamt about doing couldn’t be done. Technology simply couldn’t keep up with his demands. To pull off his funny, improvisational sets the way he wanted, he spent six years and $30,000 building a complex live setup he calls the Beardytron 5000 mkII. Chatting with him over the phone while he was on vacation in Morocco, it’s quickly apparent that he’s something of a pioneer, inventor, and very smart dude.

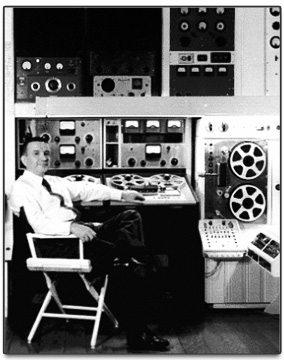

After almost an hour of falling down the technological rabbit hole with Beardyman, he asks, “Do you know Raymond Scott?” (Beginning in the 1930s, Scott was a swing/jazz composer, bandleader, and electronic-instrument inventor whose songs could be heard in Looney Tunes cartoons.) “He decided that he needed to invent a machine that could perform for him because human musicians weren’t rigid enough or capable of performing the complex music he had in his head. So he inadvertently made the world’s first sequencer. He had this thing called the circle machine with this armature with a light sensor on it that would swing around a circle of light bulbs. His dream was for the audience to hear what it was that he had in his head by virtue of a machine that would interpret the most minimal of his movements. You just selected from loads of different buttons, and it made the music.”

After almost an hour of falling down the technological rabbit hole with Beardyman, he asks, “Do you know Raymond Scott?” (Beginning in the 1930s, Scott was a swing/jazz composer, bandleader, and electronic-instrument inventor whose songs could be heard in Looney Tunes cartoons.) “He decided that he needed to invent a machine that could perform for him because human musicians weren’t rigid enough or capable of performing the complex music he had in his head. So he inadvertently made the world’s first sequencer. He had this thing called the circle machine with this armature with a light sensor on it that would swing around a circle of light bulbs. His dream was for the audience to hear what it was that he had in his head by virtue of a machine that would interpret the most minimal of his movements. You just selected from loads of different buttons, and it made the music.”

WHAT WAS MISSING

Scott’s idea to collaborate musically with machines is also Beardyman’s goal. Listen to his set in Pune, India (above) in October, and you’ll have an inkling of how his brain operates. Case in point: Midway in the set, before embarking on his next improvisational excursion, he announces, “I’m going to start a song that I wrote five seconds in the future.” His ideas manifest from seemingly nothing. He builds them up, breaks them down, dissolves them, and then transitions into something entirely new. While it suits his personality—which he describes as “quite strongly ADD”—to follow every random whim, it has taken years, and endless hours in those years, to get technology to cooperate with his needs.

Scott’s idea to collaborate musically with machines is also Beardyman’s goal. Listen to his set in Pune, India (above) in October, and you’ll have an inkling of how his brain operates. Case in point: Midway in the set, before embarking on his next improvisational excursion, he announces, “I’m going to start a song that I wrote five seconds in the future.” His ideas manifest from seemingly nothing. He builds them up, breaks them down, dissolves them, and then transitions into something entirely new. While it suits his personality—which he describes as “quite strongly ADD”—to follow every random whim, it has taken years, and endless hours in those years, to get technology to cooperate with his needs.

Beardyman started out performing in cafés with a friend playing and looping guitar while he looped his beatbox ideas, but the loopers didn’t play well together. “They’d always go out of time, and I’d go out of time with myself because I had one pedal going into another one, and it was all going everywhere,” he says.

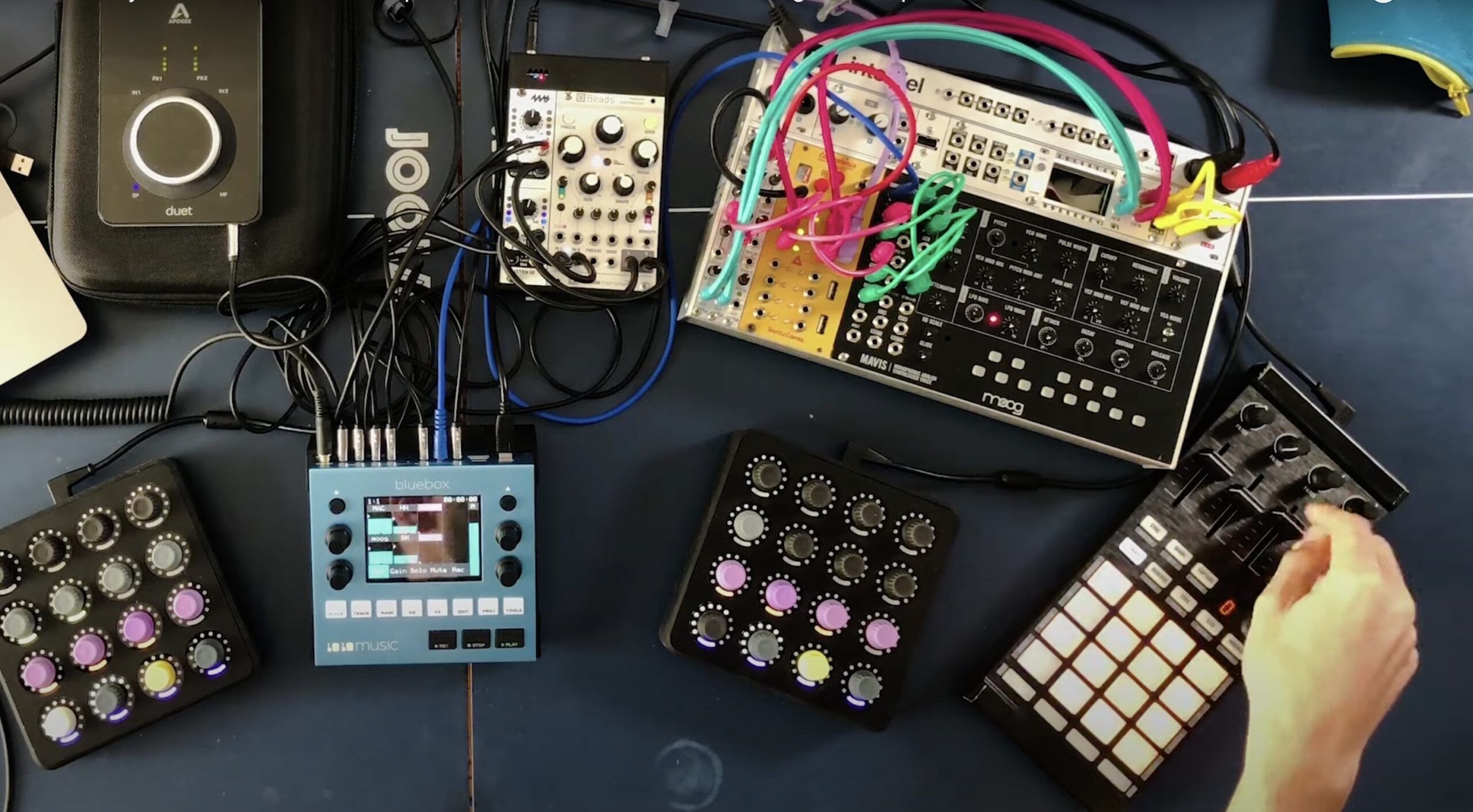

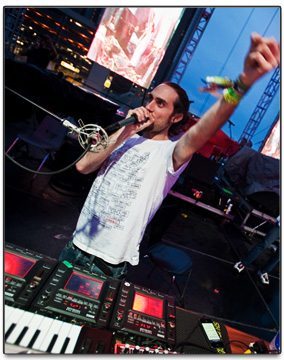

He says he’s tried out virtually every looping pedal that’s ever been made, and got close to approximating what he wanted to do with an arsenal of Korg KP3 KAOSS Pads (see them in his old setup pictured to the left). “You could do accurate subdivisions of a tempo, or multipliers of a tempo, so you could have a one-beat loop, a bar-length loop, a four-bar length loop going all at the same time, and they’d always stay in time with each other,” Beardyman says. “But whilst they were the best thing out there at the time as an effect/pseudo-looping solution, and they can resample into themselves, they do all of that very clunkily and slowly.”

He also used the single unit rackmount called Looperlative (pictured below) by Robert Amstadt. Unfortunately, Beardyman started getting electric shocks from the unit, and he couldn’t get the unit fixed because Bob became chronically ill and was unreachable for six months. “I decided I couldn’t use some dude’s invention,” Beardyman says. “It had to be a commercial product in case it broke on tour because reliability and longevity is incredibly important if you’re taking something around the world.”

Then Beardyman started using [Circular Labs] Mobius freeware inside the Plogue Bidule modular patching environment, which wasn’t reliable enough, either. After a lot of frustration, he came to the conclusion that there simply wasn’t an existing looper that he could effectively use as part of a live-production system.

Even Ableton Live had its limits. “The structure of dance music, where you have build-ups and thinning out and different kinds of drops: dead stops, rolling drops, and complex effects build-ups, Ableton is built for that,” Beardyman says. “But to do it live from scratch with no starting material—and also to be able to have your rig very, very adaptable—it’s impossible.”

One artist that Beardyman admires, Imogen Heap, has also encountered obstacles to her creativity. “ I’ve always been very dissatisfied with the way that my shows have been because for me the dream is to have a musical idea just pop into existence the moment I think of it,” Beardyman says. “There are many other people who have the same dream. Imogen Heap has an almost identical ideal that she’s trying to achieve. Hers is a bit more feminine and graceful. She has these gloves that she’s making, which fit into this insane LED suit. She’s got a team of ten people working on it, and she moves around the stage and points her wrists at objects, and it’s all gesturally based, so there’s no controller of any sort. And whilst I love the idea of having something as beautiful as that, it’s more important to me to achieve the sounds that I want, so I’ve focused on being able to make dance music live.”

One artist that Beardyman admires, Imogen Heap, has also encountered obstacles to her creativity. “ I’ve always been very dissatisfied with the way that my shows have been because for me the dream is to have a musical idea just pop into existence the moment I think of it,” Beardyman says. “There are many other people who have the same dream. Imogen Heap has an almost identical ideal that she’s trying to achieve. Hers is a bit more feminine and graceful. She has these gloves that she’s making, which fit into this insane LED suit. She’s got a team of ten people working on it, and she moves around the stage and points her wrists at objects, and it’s all gesturally based, so there’s no controller of any sort. And whilst I love the idea of having something as beautiful as that, it’s more important to me to achieve the sounds that I want, so I’ve focused on being able to make dance music live.”

THE BEARDYTRON BEGINS

After struggling with various existing combinations of software and hardware, Beardytron started working with Sebastian Lexer, a computer programmer, musician, and lecturer on the Max/MSP platform at Goldsmiths, University of London. The two started building a setup for Beardyman within Max/MSP, but there were issues with CPU power limits.

“So it became more and more clear that if I wanted to do what I needed to be able to do, I had to build from the ground up from scratch,” Beardyman says. “But some of the looping heuristics and interface strategies that we developed became test cases and proofs of concept in what now exists.”

After hitting another wall with Max/DSP, Beardyman met Dave Gamble, owner of DMGAudio and creator of plug-ins such as Compassion, EQuality, EQuick, and PitchFunk. (Gamble also built products for Focusrite, Novation, and others.) “He’s so intelligent, it terrifies me sometimes,” Beardyman says. “He’s kind of a math genius.” And it turns out he was just the right person to work on the Beardytron system, which includes eight instances of Gamble’s Compassion compressor VST, three of them on the bass channel alone. “It took me a good month or so to learn my way around [Compassion] because once you go under the hood of it, you can tweak it more than any other compressor,” Beardyman says. “Rather than component modeling, it models the mathematical processors, which go with any compressor, but all of them are tweakable, and they’re arranged in such a way that there’s a vast amount of analysis information—all these parameters—in a very legible way.”

Beardyman and Gamble also implemented 15 instances of SugarBytes’ Turnado, a multi-effect, real-time audio manipulation tool, into the system (with plans to add more). “There are several channels, which are delineated into their respective functions: pads, bass, drums, melody,” Beardyman says. “Each of them has to be channel compressed and bus compressed, all very gently massaged so that nothing gets in the way of anything else, and things are side-chained off of each other so that there’s space in the mix. There’s very subtle EQing done on them as well just to make sure that the bass and drums have dominance. And that’s taken a long time, just configuring the EQ and compression settings for the system so that there is kind of a one-size-fits all in terms of genres. I can put any genre into it and I’ve got other settings using Turnado, which allow me to sidechain or assimilate sidechaining for each different genre.”

See how SugarBytes’ Turnado stacks up against other real-time effects units in this March 2012 article.

Beardyman says he needs more than a dozen instances of Turnado to create live productions that compete sonically with popular studio recordings. “If you think about what goes into produced music these days, you see a Katy Perry track, and it sounds like some bullshit, and it’s very clean and nice and nothing seems to be getting in the way of anything else, but the mix is very loud,” he says. “But when you look at the track, there’s over 90 tracks doing very small, trifling things, which in the overall mix, help to balance everything.”

Beardman’s music doesn’t sound like Katy Perry – but he can approximate the production of many different genres, including styles ranging from dubstep to chopped and screwed. Within Turnado, Beardyman has created hundreds of presets that he’s created for various genres of music he taps into live, and using the “Dictator” mode in Turnado (visible in the above screenshot), he can use one fader to control up to eight different effects at once. “The amount of effects used in modern music is just staggering, and the amount of pre-programming it takes to get the kind of effects that you want is insane,” he says.

For Beardyman, the name of the game is being able to control things like high- and low-pass filtering, build-ups and drops, and muting and unmuting of channels in real-time with just two hands: “Without having this many instances of the world’s most controllable multi-effect, there would be literally no way for me to do it.”

And those instances are inextricably linked: “A lot of them feed off each other, so doing one thing on one will cause a macro to happen on another one for build ups and drops,” Beardyman says. “I’ve got all these intricate things worked out within the system so that, almost without thinking about it, it produces dance music of its own accord. But obviously, I’m driving it.”

Helping him drive it are three iPads, two of which control the Beardytron and one that uses apps for extra noises. He also has keyboards, Native Instruments Guitar Rig, and Rob Papen’s delay as part of the setup.

COMPUTER BEHAVIOR

According to Beardyman, the biggest challenge of building the Beardytron was implementing a looper and effects with minimal CPU drain and latency. On that topic, Beardyman is particularly guarded. “I can give you some stats about it, and I can tell you about what it does, but I can’t tell you necessarily how it does it if I think it’s something that needs to be patented. Applying for a patent is so expensive. And once you’ve got something patented, it’s available for everyone to see, and all they have to do is make five significant changes to it, and then legally they’re in the clear and they’ve stolen your idea. And also, if you don’t have a legal team and the financing behind you to be able to sue in case of infringement on your patents, then it’s not worth the paper it’s written on. So secrecy is the name of the game when you’re going to release software. But I do want to make this thing available to everyone who is a looper or wants to do looping.”

That said, Beardyman offers a few clues about what makes his system so powerful. “There’s a multi-threading engine going on within the looper,” he says. “Only major DAWs have this kind of thing where the CPU is splitting the signal of the different channels between the CPUs and apportioning according to what’s going to be the most efficient audio-processing routine. So that’s why we’re able to have so many instances of Turnado.”

Almost every week, Beardyman and Gamble meet up to see where they can streamline the Beardytron 5000 mkII. “I’ll realize that there was an inefficiency in my set that can be surmounted and that one little tweak will make all the difference,” he says. “I’ll realize that I’m doing two actions at the same time every time I do them, and I’m like, ‘Well, let’s link those together.’ So very slowly, I’m figuring out a language within the system.”

TOP SECRET LOOPING TECH

Beardyman is secretive about the Beardytron looper. But allegedly, it’ll do what loopers can do in a DAW, such as multiplying or dividing according to a certain factor, overdubbing, or replacing a section of the loop. Only with Beardytron’s looper, it’ll do it all in one audio file. While creating the looper, Beardyman and Gamble had to make tons of small decisions. “You can undo; you can redo,” he says. “But we had to decide what undo and redo meant. How many times can you undo or redo? We had to test how much RAM that would take up, how fast the action would take to perform, and what an undo would mean. Does an undo mean one iteration of a loop, or does undo mean the last insert that you did? Can you undo all actions, or can you only undo certain ones? We had to answer all these questions.”

Beardyman is secretive about the Beardytron looper. But allegedly, it’ll do what loopers can do in a DAW, such as multiplying or dividing according to a certain factor, overdubbing, or replacing a section of the loop. Only with Beardytron’s looper, it’ll do it all in one audio file. While creating the looper, Beardyman and Gamble had to make tons of small decisions. “You can undo; you can redo,” he says. “But we had to decide what undo and redo meant. How many times can you undo or redo? We had to test how much RAM that would take up, how fast the action would take to perform, and what an undo would mean. Does an undo mean one iteration of a loop, or does undo mean the last insert that you did? Can you undo all actions, or can you only undo certain ones? We had to answer all these questions.”

Other loopers such as Mobius or the looper within Ableton have those capabilities, Beardyman says, “but it’s the interaction between the effects and the loops [in the Beardytron], which make it possible to do in real time.”

A man who has clearly done his homework, Beardyman references mathematician and pioneer of computer science Alan Turing, who in 1950 tested a machine’s artificial intelligence with his Turing test by asking a human judge to distinguish between a machine and an actual human’s answers: “You’re having a conversation with a computer, but you don’t realize it’s a computer.”

But Beardyman is more fascinated than spooked by what he and Gamble have been able to create. “To an extent, the machine has become a kind of dance-music creation device, which increasingly relies less and less upon my whims and obeys the rules of music,” he says. “As I use the machine, I figure out more subtle ways that it can control itself, and I just put in the inspiration. That sounds incredibly wanky, but that is the end game, to make it so that anyone can put sounds into it, and with just a couple macro parameters, decide how it’s going to behave.”

Kylee Swenson is a guest contributor to DJ Techtools – read her previous article for us on how Keith MacMillen Instruments funded and built the QuNeo with the helps of thousands of fans who paid in advance.

Header photo credit: Jim Hanner.

Check out the long video of Beardyman using his new setup on December 1st in Bulgaria in the below video: