Two decades after the original Summer of Love in 1967, Britain exploded into two seasons of euphoria, capturing the minds of British youth to the sound of acid house. Emulating the free spirit and hedonism of the 60s, the summers of 88 and 89 helped define the zeitgeist of that era in rave culture. Today Akhil Kalepu takes us back to this historical moment for raves in Britain.

Crash Course for the Ravers

Curiously enough, the word rave actually predates electronic music. The term was originally used to describe parties thrown by the beatnik community in SoHo, London. Early rock acts used the word in songs, but before modern EDM culture, the term rave was most notably used in an experimental electronic music performance called, Million Volt Light and Sound Raves, performed at the London Roundhouse in 1967 and featuring the unreleased “Carnival of Light” by Paul McCartney. The word rave fell out of use during much of the 60s and 70s, save for David Bowie ironically using it in his song “Drive-In Saturday”.

By the mid 80s, electronic dance music was starting to take over Manchester and later London, as well as a revival of the word rave. The scene was largely influenced by the mod culture and Northern Soul movement in the 60s and 70s, known for their all night dance parties to the sound of American soul music, particularly the uptempo style of Motown.

Various subcultures that the scene evolved into, like mod revivalists and apolitical skinheads, were known for including both black and white communities, in addition to having a taste for soul, ska and early reggae music. While the word rave might have been a throwback to its use in early rock, it is more likely that the term was revived through its use in Jamaican communities who participated in the burgeoning youth culture of 80s Britain.

Learn more about the history of rave.

We Have Achieved Orbital Velocity

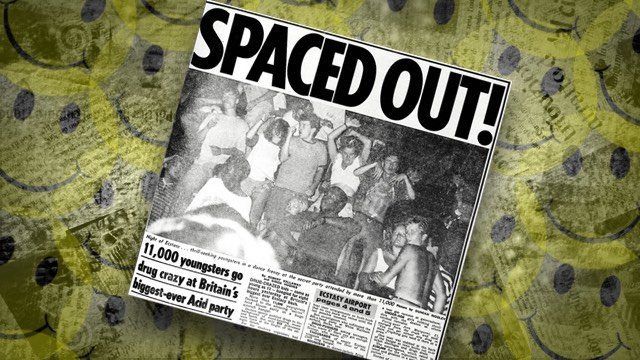

The bleak economic environment at the time had brought the UK’s textile industry to a halt, forcing many factories and warehouses to be shuttered and abandoned. These secluded spots ranged from industrial sites to empty fields, and were the perfect venues for un-licensed parties fueled by illicit substances. LSD was experiencing a minor resurgence, but MDMA was absolutely the soup de jour, encouraging a spirit of love, empathy and community, in addition to providing boatloads of energy and sheer euphoria.

“It definitely took ecstasy to change things. People would take their first ecstasy and it was almost as if they were born again.” – Mark Moore*

By the late 80s, acid house had made its way into venues like Danny Rampling’s legendary Shoom:

“You will always get people saying ‘My mate played “acid house” back in 1984,’ and some of the records had been around for a couple of years, but it wasn’t until 1988 that it exploded and took the whole country by storm.” – Danny Rampling*

While the instutionalized club scene was scrambling to rebrand itself as rave culture, clubbers in London and the rest of England were developing a taste for something even more daring.

The explosion of unlicensed parties in 88 and 89 can in part be attributed to the lack of late night venues. Acid house clubs like Nicky Holloway’s Trip were notorious for run-ins with the police.

“At the Trip, people would refuse to go home at the end of the night. The roads would all be blocked, and people would be dancing in the fountains at the bottom of Centrepoint. The police would just be laughing because they had absolutely no idea what was going on. They didn’t know what ecstasy was at this point, so they just couldn’t understand.” – Nicky Holloway*

UK laws made after-hours clubbing difficult, feeding a demand for ravers who wanted to keep on dancing. To avoid raids, events began utilizing inconspicuous warehouses and empty fields, allowing ravers to dance through the night. These locations were linked by the recently completed London M25 Orbital, the city’s new motorway which circled the city and provided easy access to the countryside. In addition to calling party advertisements, Londoners could simply drive on the highway and follow the music to a secret rave.

Modern rave culture was in full swing by the summer of 88. Groups like Sunrise brought the scene to new heights with several large parties like Burn It Up, Midsummer Night’s Dream and Back to the Future. These gatherings brought international DJs and huge sound systems, in addition to lights, lasers, fog, amusement park rides, and a general feeling of community. Rival hooligan gangs could dance together without conflict and people looked out for each other’s well being.

The soundtrack to the summer was predominantly acid house, featuring the classic squelching bass sound of the Roland TB-303 (the Roland AIRA TB-3 is a modern reimagining of this classic bass synthesizer.) The genre originated from Chicago in the mid 80s, before being adopted in Manchester and then London. Inspired by a trip to Ibiza, several key DJs and clubs like Paul Oakenfold’s Future began shifting tastes from hip-hop and rare groove to acid house and electronic dance music.

“The very first people to get into it were those from London, Manchester and Sheffield who had been out working in Ibiza in the summers of 1986 and ’87 and been exposed to it there.” – Terry Farley*

*Source: The Guardian.

Coming Down and Back Up Again

The sheer intensity of those two summers died down after local council began clamping down on the unlicensed parties. Musical tastes were beginning to splinter when the 90s rolled around, making large parties difficult to get licensed and promoted. The phenomenon of free parties had reached its peak in 1992 with the infamous Castlemorton Common Festival.

The weeklong party was unintentionally created when police prevented the previously held Avon Free Festival from happening. Somewhere between 20,000-40,000 of ravers were instead gathered on Castlemorton Commons for five days of non-stop dance music. Big DJs and media coverage incited a surge in crowds as well as a nationwide moral panic.

While the party had to die down on its own, the party and several drug-related deaths inspired the Criminal Justice and Public Ordinance Act of 1994, aiming to guard the public from an “emission of a succession of repetitive beats”. The bill was widely ridiculed for its ridiculous definition of rave music and complete ineffectiveness, as by this time, legal parties were the main venue for ravers with groups like Helter Skelter supporting the scene through licensed events. British electronica band Autechre released the Anti-EP mocking the bill:

“Warning. ‘Lost’ and ‘Djarum’ contain repetitive beats. We advise you not to play these tracks if the Criminal Justice Bill becomes law. ‘Flutter’ has been programmed in such a way that no bars contain identical beats and can therefore be played under the proposed new law. However, we advise DJs to have a lawyer and a musicologist present at all times to confirm the non repetitive nature of the music in the event of police harassment.” – Wikipedia

The impact from the Second Summer of Love can still be felt today, with the rise of EDM and DJ driven mega festivals thrown around the world. Despite the inevitable commercialization of the scene, the free spirit of the original rave generation is strong and will only grow.

Akhil Kalepu is a producer and DJ from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. You can check out his work at theinfamousAK.com.

Looking for more articles on rave culture? Learn more with these articles: