Digital and analog DJing may employ very different tools, but they all are aimed at the same goal: blending finished songs together into a continuous mix. Effectively accomplishing that with any tool requires the same fundamental knowledge of music, song structure and frequency behavior. Because new technology now lets people enter the world of DJing much easier, it seems appropriate to go back to the basics and cover some fundamental principles of DJing which everyone, new and old, can always use.

SONIC SOUP

As his or her most fundamental job, a DJ keeps the volume of the set consistent and even. Volume is perceived as energy, so erratic changes in sound levels will confuse and frustrate your dancefloor. Even if you do nothing else other than play one song after the next without mixing, it’s critical that each song has the same perceived volume. Later on you can use volume as a tool to create excitement intentionally but everyone must learn to walk before running.

Problem: Uneven recording levels. Although every producer tries to turn up his or her final mixes to 11, many songs come out of the music plant with different volumes. If you play a sequence of songs back to back, chances are high that they will vary wildly in volume.

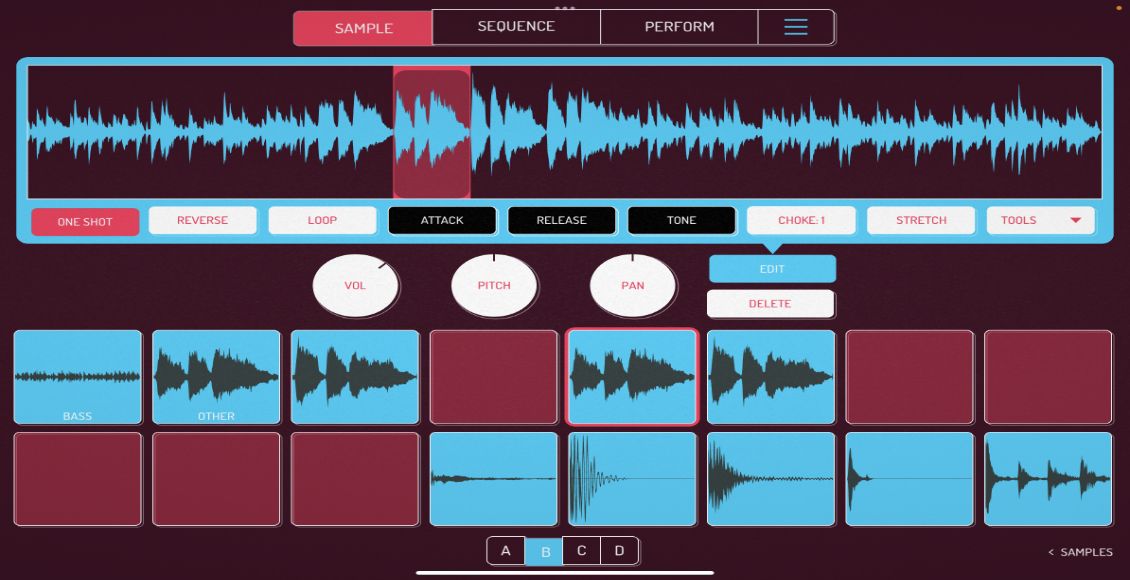

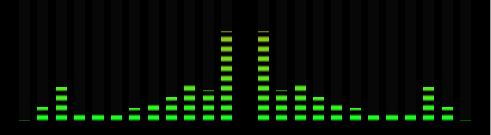

Solution: Use the meters. Every decent DJ mixer and almost all DJ software show you a visual level of each channel’s volume levels through LED meters. Using your Gain knob, adjust each track until both channels’ meters match just about perfectly. That means they are peaking at the same level and demonstrate a similar movement when the beats hit.

Take note: Programs such as Serato Scratch and Native Instruments Traktor offer auto-gain features that will solve this problem very accurately without any thought from you. It’s a good idea, however, to practice mixing with this feature off so you can get the hang of it on your own.

Problem: 1 + 1 = 2. If you add two songs together at full volume, your loudness will be almost doubled, but when the mix is over, the energy will fall back again.

Solution: Always mix in equal parts. As you bring a track in, the other song’s level should be brought down in equal amounts. This way the sonic power of one track is always replacing the other’s, so theoretically, volume levels will stay the same before, during and after the mix. Some people choose to mix with crossfaders because they can perform this function in one motion, equally fading out one track as the other comes in. The crossfader is rarely a perfect solution, however, because the exact blend of each track is never 50/50, so many DJs prefer to use the input faders instead, adjusting the precise mix by ear.

Take note: It’s inadvisable to have both fader levels higher than 90 percent at the same time because that gives you nowhere to go, and the master volume will rise and fall with each mix.

THE BALANCING ACT

Once you get the hang of carefully blending each song together and keeping your overall level even, it’s time to move on to the next technique.

Problem: Not all songs were created equal. Let’s be honest, some tracks bump and some tracks don’t. There is nothing more depressing than going from a big anthem to a track that just does not have enough oomph.

Solution: Add EQ to taste. Unfortunately, most DJ equipment does not allow you to visually monitor the frequency range of a song. Instead, you must rely on a good pair of headphones and your better judgment to fix things by ear. Need more bump? Add some extra low frequency, but be careful not to crank it up too much or it will drown out everything else. Perhaps the track sounds dull? Add a healthy amount of high-end zip. If you have a hard time understanding the words, put some extra mid-range in the mix.

Take note: There is a well-known engineering technique most DJs aren’t aware of. Instead of boosting frequencies, try taking away the competing ones. For example, if you need some more kick drum, cut out some mid frequencies, boost the highs just a touch and bring up that channel’s gain a few decibels. Result: more kick without a muddy mix.

Problem: Track levels are equal, but the energy gets lost. The ear picks up on patterns in the music and slowly shifts our attention from the outgoing to the incoming patterns. Sometimes both patterns work well together, and even though you need to make room sonically, you don’t want to lose the parts that are keeping the energy up.

Solution one: Cut out the old track’s low end entirely. You can think of each mix as having an overall frequency budget of 100. In a balanced mix, each track is allotted 50 units of that budget between the frequency ranges. If you don’t want to turn down a song but need to make room for a new song, then cut out the frequency band that eats up most of your budget — the low end. This technique should be used if the old song has a vocal or synth line that you want to keep present in the mix while allowing the new song room to take over the primary rhythm.

Solution two: Cut out the high and the low frequencies entirely. Oftentimes two songs sound great together, but when the mix is over, the energy drops big time. Sometimes that is not because of gain in-balance, but rather the older song just had a much better kick. So set a loop at the end of a song where there is no bass line, cut out all the other frequencies and keep that kick loop running for as long as possible under the new track.

Take note: Dramatically cutting frequencies to make your mixes work is a good tool, but you shouldn’t rely on it entirely; it can make the songs sound unnatural and bring attention to your mixing when you want the mix to remain transparent. Some of the most effective mixes are those during which full-frequency tracks are gently brought in and out of the mix. In fact, many of the world’s famous DJs swear by the old Urei mixers, which didn’t have any EQ adjustments at all.

For more digital dj basics check out this article which talks about song structure and making songs work together musically.