This article is another great historical piece from guest contributor Akhil Kalepu, and this time he’s chosen to tackle the history of the turntable. Read on to hear about how it all started out with recorded sound, phonautographs, and cylinders of sound in the 1800s, and how the technology progressed from there.

With Panasonic’s recent announcement at CES, the Technics makes a much-wanted return as the SL-1200G and SL-1200GAE. Set for release later this year, the new models mark 44 years since the original SL was released in 1972, though the history of the turntable goes back further than that. Originally invented more than a century ago, this is the story of the foundation of modern DJ culture first came about.

Riding the Waveforms

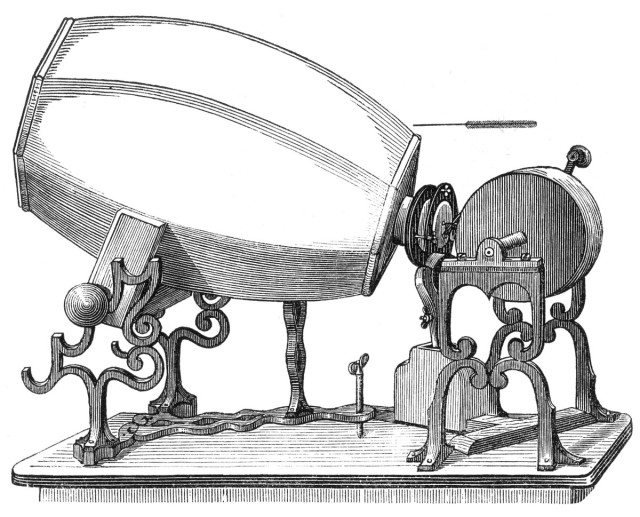

The original phonograph was famously created in 1877 by a young Thomas Alva Edison, though the recorded sound was first pioneered by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville. In 1853 the French printer began researching methods of transcribing sonic waveforms for studying acoustics. His device was purely for visual purposes, giving people a primitive method of studying amplitude envelopes and frequencies. The device, called a phonautograph, recreated mechanisms of the human ear, utilizing a horn to funnel in sound and thereby transmitting them to a stylus, which would record the vibrations onto a membrane of lampblack (soot from an oil lamp) wrapped around a hand-cranked cylinder.

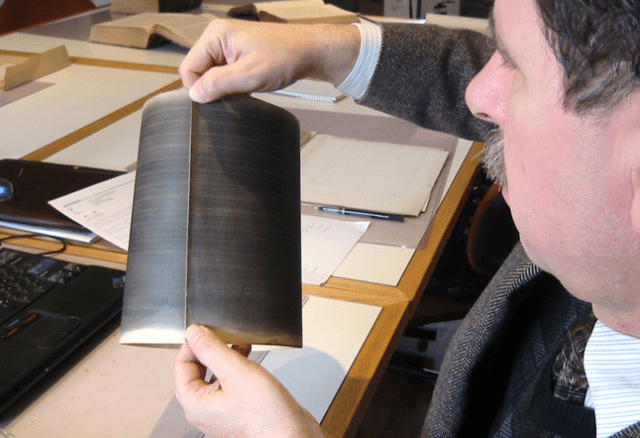

Scott was awarded a patent for his invention in 1857, but his phonautograms were mostly lost to history until very recently in 2008. Thanks to advances in optical technology, audio historians were able to scan high quality images of the original cylinders and encoded the waveforms into digital audio files. The final product revealed Scott’s rendition of the French folk song “Au clair de la lune,” the earliest known audio recordings in history (listen below), predating Frank Lambert’s Experimental Talking Clock, which was recorded on a phonograph in 1878. Prior to these recreations, the French poet and inventor Charles Cros came up with a similar device nearly two decades after the release of the phonautograph.

Voice of the Past

If acoustic vibrations could be etched into grooves, Cros correctly theorized that the reverse process could be used to convert the grooves back into the original sound. Photoengraving technology was already in use, allowing him to duplicate the delicate phonautograms into more durable metal cylinders. By the end of April in 1877, Cros submitted a paper to the Academy of Sciences in Paris, dubbing his invention the paleophone, known in French as “la voix du passé.” An article was published about the device on October 10, 1877, just one month before Edison would introduce his phonograph to the world, though Cros was not a man of means and couldn’t pay for a prototype to be made. Fortunately, the man was able to get his due credit in December when his paper was reviewed by the French Academy of Sciences.

Despite the timing, Edison and Cros are believed to have independently invented the phonograph. While Cros pioneered the idea of using a disc record, Edison favored cylinders wrapped in tinfoil as he believed having all the engravings on the outside of the disc would keep them playing at the same velocity, therefore the sound was more “scientifically correct.”

Edison originally wanted to create a “telephone repeater” and he envisioned many applications other for his phonograph, though several demonstrations failed to raise interest beyond its brief novelty. The young inventor did receive widespread recognition for his ingenuity, but Edison chose to purse research into electric light, selling the rights to the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company in 1878 and leaving others to perfect his device.

Volta Improvements

Shortly after the release of the phonograph, associates at Alexander Graham Bell’s Volta Laboratory began research into an improved design, calling their invention the graphophone. Charles Summer Tainter and Alexander’s cousin Chichester Bell made several innovations that helped bring recorded music to the mass public. Instead of tinfoil, the lab experimented with cardboard cylinders coated in wax, thereby enhancing audio fidelity and durability, even designing a machine to mass-produce them. Electric motors replaced hand cranks and wind-up clocks, and the cylinders were recorded in a lateral “zig zag” pattern instead of vertically, the method that would be adopted for disc records.

By 1885 Volta Laboratory filed for a number of groundbreaking patents including the Dictaphone and the photophone, which was a wireless telephone and precursor to fiber-optic communication. The late 1880s saw a number of companies and sub-companies enter the phonograph business, though the industry wasn’t very profitable until the next decade. Volta and Edison were eventually folded into the North American Phonograph Company, consolidating the rights and capitalizing on the phonograph name, though most of the business was in dictation machines and not entertainment. It wasn’t until the turn of the century when Louis Glass of the Pacific Phonograph Company popularized the use of coin-operated machines for entertainment purposes. One of the companies born in this time was the Columbia Phonograph Company, which would go on to become Columbia Records

Format Wars

It was around this time that one of the original format wars began. Charles Cros originally theorized the laterally cut disc format, but it was Emile Berliner, a German-American inventor who first brought them to market in the 1890s with the release of his Gramophone, named to differentiate itself from the phonograph and graphophone. While brand specific term gramophone didn’t last, its nickname did live on through the Grammy Awards, whose trophy depicts a vintage disc machine-made by the Victor Talking Machine Company.

The public continued to use the term phonogram for both disc and cylinder players, which were competing for market dominance at the turn of the century. While the recording technology for cylinders was superior than gramophone recording, Berliner argued that his format had more commercial value. Discs were easier to mass-produce and stamp, as well as being convenient for storage. Eldridge R. Johnson, who co-founded Victor with Berliner, was able to increase the disc’s audio fidelity to that of a cylinder, and even Edison began producing discs in 1912 with the Edison Disc Record.

The beginning of the 20th century also brought about the adoption of radio transmission, with the first commercial license going to KDKA Pittsburgh in 1920. This new mode of communication brought people unprecedented access to news and music, though most of the content were live as musicians didn’t want their records played on radio at the times. Some juke joints and phonograph parlors began using coin-operated devices, as well as player pianos reproducing music off of paper rolls (a precursor music language to MIDI?), but the availability of music in the public space led to a decline in interest for personal record players. This all changed after World War II with the introduction of long-playing records, or LP albums. This new medium would go on to become the foundation of popular music culture, giving rise to the DJ and creating the seeds for modern electronic music.

Akhil Kalepu is a producer and DJ from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. You can check out his work at theinfamousAK.com, or by reading more of his work on DJTT below: