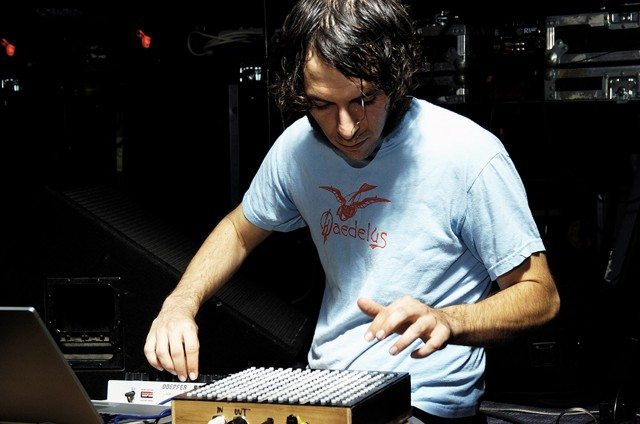

If you think watching electronic music live is boring, you’ve clearly never watched Daedelus go crazy with his Monome. Born Alfred Darlington, the Los Angeles-based producer is the Van Halen of the Monome controllerism scene. In today’s interview, we talked with him about his favorite gear, the state of electronic music, and his work with MIT engineers that will change musical performances forever.

Real Name: Alfred Darlington

What He Does: Producer/DJ/Multi-

Current City: Los Angeles, CA

For Fans Of: Dabrye, Prefuse 73, Flying Lotus

Latest Release: Drown Out (Anticon)

WHO IS DAEDELUS?

“I knew I wanted to be a musician since I was very young,” says Alfred Darlington. “As kids encounter that time honored question about what you wanna be when you grow up, my answer has always been musician, since I was like seven or eight.” But, his musical journey to becoming Daedelus didn’t begin with electronica.

“I started being a more traditional instrumentalist, playing double bass and bass clarinet; these instruments that are just incredibly acoustic. Although I was a fan of electronic music from a young age as well, I had no idea how people did it. I had no idea how synthesis worked.”

Up until the late ’90s, Darlington saw production as a mystery, until he finally decided to give it a shot himself. His first foray into electronic music wasn’t on a synth, sampler or drum machine. It was much simpler.

“The first piece of gear I used was a 4-track, where you could manipulate tape speed to get unearthly sounds.”

He would also experiment with pedals, hacking them and tinkering with the different noises that would occur due to battery sags. This began a career long fascination with using devices in ways they weren’t originally intended. He points to Roland’s infamous TB-303, which was intended to be an accompaniment tool for guitarists. “It’s one of those things where it totally failed in the given market it was made for,” he says. “But the way people hacked it; they way they basically designed a whole genre of music around it, changed it fundamentally.”

CONTROLLER OF CHOICE: MONOME

These days, he’s best known for his work with the Monome, a minimalist, multi-use, grid-based MIDI controller. He stumbled onto the device in 2003 after playing a show in San Diego with it’s main inventor, Brian Crabtree. Before that, Darlington had depended on hardware to recreate his studio sounds live.

“If you wanted to perform the music, you had to bring your desktop out to shows, which people did. That was bananas […] Or, you basically got a whole bunch of hardware and you cobbled it together to make your sounds. I had been in that vein.”

His main piece was a Yamaha A-3000 sampler, but he quickly grew tired of the limitations it presented. “I only had ten fingers and at most they could change one or two parameters at a time. It felt really slow.” When he first saw the Monome in action, Darlington says it blew his mind.

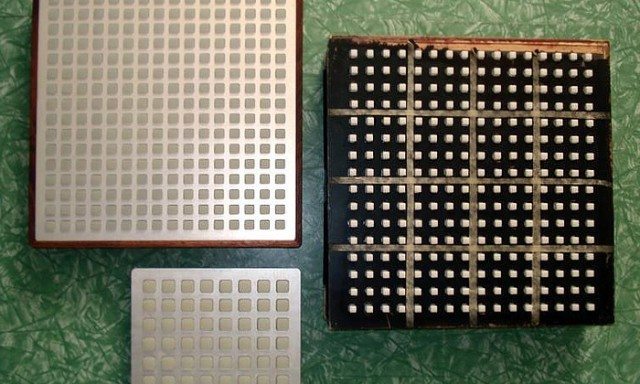

His love for the Monome is evident as he describes it’s various uses and functions. But, when he starts talking about it’s buttons, the excitement hits a fever pitch. “I have become a fetishist for button action,” he says, cracking up. “That sounds really dirty, but I don’t mean it that way.” Darlington is particularly interested in the amount of press that buttons have, and they way they react with your fingers. He also favors them largely over knobs, which don’t provide the amount of control he requires. “This is kind of silly, but when you have a knob, it takes a bunch of fingers to manipulate a knob,” he explains. “A button is much more easy and much more linear.”

When asked how the Monome compares to other controllers in the field, Darlington says there’s a variety of differences. He’s also quick to point out that the Monome came before them. “There’s a lot of people who have seized the grid system as being a really valid one,” he says, referring to Novation’s Launchpad and Akai’s APC. “There’s even a new version of Serato [referring to the Slicer], where it maps the grid of buttons to certain moments in the song. There’s a lot of people catching up.” But for him, it all goes back to those buttons. “Not to say that this is better or worse. It’s just whatever you’re used to. I just particularly like the way the Monome presses. There’s a definitive press, and yet it’s also gentle ,” he says. “You can really get into it.”

Darlington’s main sample manipulator is the Monome Two Fifty Six, named for the amount of buttons it’s grid encompasses. He uses an application called mlr to run it – available for free at monome.org. You can see lots of his amazing live performances with the device on YouTube, but he’s quick to stress that he also incorporates the machine into his studio set-up too: “I generally keep it in the studio because I like the decisions I make live.”

AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION

Darlington is so obsessed with the way devices work and interact, that’s he’s currently collaborating with people that come from the MIT Media Lab to create new devices and technology for music creation and performance. His ideas revolve around changing the way that audiences interact with the performer. Using Haptics, he’s exploring systems that would allow concertgoers a chance to be a vital part of the show. “[It’s] this kind of holistic idea that this person is adding their own part of the performance, but also being performed on – literally.” He’s not sure about the commercial implementation of such a concept, but Darlington says the technology is there – “We’re not far away from this at all,” he adds.

Keeping the audience engaged is very important to Darlington. “I think there’s an act that a lot of DJs employ where everything is so sewn up,” he says. “There’s a lot of flash and bright lights and production that goes into EDM shows. This genre of music has gotten bigger and bigger and it’s occupying stadiums, and there’s a lot of coordination between a team of people. But, what increasingly happens is music stops being present.” He welcomes the attention and popularity electronic music has received in recent years. He offers praise for people like Skrillex, and sees it as a gateway drug for those who wish to go deeper. But he’s worried about the effect that big money will have on performances. “If we keep on pursuing this idea of more and more lights and less and less art activity, the dance aspect is going to go away, and people are just going to go to a concert to listen. I like this idea of keeping the dance in the mix, the idea of motion and interactivity between the audience and the performer.”

This brings up Daft Punk’s Grammy performance, which received criticism from people who were angry that the duo were essentially doing the electronic music equivalent of lip-synching. “Who thinks that’s the future of performance?,” Darlington asks. He thinks fans not only deserve better, but they also are becoming aware of the sham. “The audience senses that. They sense that they’re watching a really grandiose movie, but essentially they’re all standing up and paying $50 to watch a movie.” The key for him is to do the opposite, and take the secrecy out of it. “I face my equipment forward so they can see what the action is on the Monome.” He also invites the audience to be more involved. “Just like I have a say in their evening, hopefully they have a say in mine. Together, we kind of go somewhere. I try to stay as present as possible.”

STUDIO GEAR + PRODUCTION ADVICE

In the studio, he’s an avid collector of Moog’s analog effect modules, Moogerfoogers, owning almost all of the units except the Bass Murf – probably a big part of why he’s playing Moogfest next month. He also is finishing up two albums. One is a collaboration with Grammy-nominated saxophonist Ben Wendal. Working with other artists allows him to step outside of his usual surroundings. “I love the aspect of being a composer, producer, and working in that space, but I don’t wanna stare at myself in a screen all day. That isn’t what I signed up for.”

When it comes to advice for aspiring producers, Daedelus offers some simple advice:

“It’s challenging nowadays to tell people that there’s any one starting place. I know so many different people who’ve started on different kinds of equipment and have made great music. So, it isn’t like I can tell people, ‘oh get Ableton,’ ‘get Reason,’ or ‘get Acid’, or ‘get Pro Tools’, or any other program to start with. I’ve heard people do amazing things with programs or hardware.”

Instead he encourages people to utilize whatever technology is at their disposal and to try to really understand the music they are interested in. His main suggestion is to do a remix:

“I think in the process of a remixing a song you have to start to understand and wrestle with how it works. You are developing a voice that may become house or techno or whatever, but you have to start somewhere. That’s on the shoulders of someone else. Everyone is kind of working that way.”

He’s confident that young producers will carry electronic music forward, solely due to their naivety, which he sees as a positive trait. “The fact that Jimi Hendrix existed means that you should never play guitar,” he says with a laugh. “When you’re young and dumb – for lack of a better term – you don’t know any better and you can be as good, if not better than Jimi, you know, because it’s not a competition. That’s not what music is about.” He adds: “That’s a beautiful thing and I think that sense of innocence does win. It tends to win.”

Daedelus playing a few shows this summer, including Moogfest, which is a five day festival dedicated to the synthesis of technology, art and music. The festival honors the creativity and inventiveness of Bob Moog and pays tribute to the legacy of the analog synthesizer with an experimental lineup including Kraftwerk 3D, Pet Shop Boys, Flying Lotus & more. Single day passes and 5-day GA passes available here.